4 Early Childhood

Our discussion will now focus on the physical, cognitive and socioemotional development during the ages from two to six, referred to as early childhood. Early childhood represents a time period of continued rapid growth, especially in the areas of language and cognitive development. Those in early childhood have more control over their emotions and begin to pursue a variety of activities that reflect their personal interests. Parents continue to be very important in the child’s development, but now teachers and peers exert an influence not seen with infants and toddlers.

4.1 Physical Development in Early Childhood

Summarize the overall physical growth

Describe the changes in brain maturation

Describe the changes in sleep

Summarize the changes in gross and motor skills

Describe when a child is ready for toilet training

Describe sexual development

Identify nutritional concerns

Overall Physical Growth: Children between the ages of two and six years tend to grow about 3 inches in height and gain about 4 to 5 pounds in weight each year. Just as in infancy, growth occurs in spurts rather than continually. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000) the average 2-year-old weighs between 23 and 28 pounds and stands between 33 and 35 inches tall. The average 6-year-old weighs between 40 and 50 pounds and is about 44 to 47 inches in height. The 3-year-old is still very similar to a toddler with a large head, large stomach, short arms and legs. By the time the child reaches age 6, however, the torso has lengthened, and body proportions have become more like those of adults.

This growth rate is slower than that of infancy and is accompanied by a reduced appetite between the ages of 2 and 6. This change can sometimes be surprising to parents and lead to the development of poor eating habits. However, children between the ages of 2 and 3 need 1,000 to 1,400 calories, while children between the ages of 4 and 8 need 1,200 to 2,000 calories (Mayo Clinic, 2016a).

4.1.1 Brain Maturation

Brain weight: The brain is about 75 percent its adult weight by three years of age. By age 6, it is at 95 percent its adult weight (Lenroot & Giedd, 2006). Myelination and the development of dendrites continue to occur in the cortex and as it does, we see a corresponding change in what the child is capable of doing. Greater development in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain behind the forehead that helps us to think, strategize, and control attention and emotion, makes it increasingly possible to inhibit emotional outbursts and understand how to play games. Understanding the game, thinking ahead, and coordinating movement improve with practice and myelination.

Growth in the Hemispheres and Corpus Callosum: Between ages 3 and 6, the left hemisphere of the brain grows dramatically. This side of the brain or hemisphere is typically involved in language skills. The right hemisphere continues to grow throughout early childhood and is involved in tasks that require spatial skills, such as recognizing shapes and patterns. The corpus callosum, a dense band of fibers that connects the two hemispheres of the brain, contains approximately 200 million nerve fibers that connect the hemispheres (Kolb & Whishaw, 2011). The corpus callosum is illustrated in Figure 4.2.

The corpus callosum is located a couple of inches below the longitudinal fissure, which runs the length of the brain and separates the two cerebral hemispheres (Garrett, 2015). Because the two hemispheres carry out different functions, they communicate with each other and integrate their activities through the corpus callosum. Additionally, because incoming information is directed toward one hemisphere, such as visual information from the left eye being directed to the right hemisphere, the corpus callosum shares this information with the other hemisphere.

The corpus callosum undergoes a growth spurt between ages 3 and 6, and this results in improved coordination between right and left hemisphere tasks. For example, in comparison to other individuals, children younger than 6 demonstrate difficulty coordinating an Etch A Sketch toy because their corpus callosum is not developed enough to integrate the movements of both hands (Kalat, 2016).

4.1.2 Motor Skill Development

Early childhood is the time period when most children acquire the basic skills for locomotion, such as running, jumping, and skipping, and object control skills, such as throwing, catching, and kicking (Clark, 1994). Children continue to improve their gross motor skills as they run and jump. Fine motor skills are also being refined in activities, such as pouring water into a container, drawing, coloring, and buttoning coats and using scissors. Table 4.1 highlights some of the changes in motor skills during early childhood between 2 and 5 years of age. The development of greater coordination of muscles groups and finer precision can be seen during this time period. Thus, average 2-year-olds may be able to run with slightly better coordination than they managed as a toddler, yet they would have difficulty peddling a tricycle, something the typical 3-year-old can do. We see similar changes in fine motor skills with 4-year-olds who no longer struggle to put on their clothes, something they may have had problems with two years earlier. Motor skills continue to develop into middle childhood, but for those in early childhood, play that deliberately involves these skills is emphasized.

Children’s Art: Children’s art highlights many developmental changes. Kellogg (1969) noted that children’s drawings underwent several transformations. Starting with about 20 different types of scribbles at age 2, children move on to experimenting with the placement of scribbles on the page. By age 3 they are using the basic structure of scribbles to create shapes and are beginning to combine these shapes to create more complex images. By 4 or 5 children are creating images that are more recognizable representations of the world. These changes are a function of improvement in motor skills, perceptual development, and cognitive understanding of the world (Cote & Golbeck, 2007).

The drawing of tadpoles (see Figure 4.4) is a pervasive feature of young children’s drawings of self and others. Tadpoles emerge in children’s drawing at about the age of 3 and have been observed in the drawings of young children around the world (Gernhardt, Rubeling & Keller, 2015), but there are cultural variations in the size, number of facial features, and emotional expressions displayed. Gernhardt et al. found that children from Western contexts (i.e., urban areas of Germany and Sweden) and urban educated non-Western contexts (i.e., urban areas of Turkey, Costa Rica and Estonia) drew larger images, with more facial detail and more positive emotional expressions, while those from non-Western rural contexts (i.e., rural areas of Cameroon and India) depicted themselves as smaller, with less facial details and a more neutral emotional expression. The authors suggest that cultural norms of non-Western traditionally rural cultures, which emphasize the social group rather than the individual, may be one of the factors for the smaller size of the figures compared to the larger figures from children in the Western cultures which emphasize the individual.

| Age | Gross Motor Skills | Fine Motor Skills |

|---|---|---|

| Age 2 |

|

|

| Age 3 |

|

|

| Age 4 |

|

|

| Age 5 |

|

|

4.1.3 Toilet Training

Toilet training typically occurs during the first two years of early childhood (24-36 months). Some children show interest by age 2, but others may not be ready until months later. The average age for girls to be toilet trained is 29 months and for boys it is 31 months, and 98% of children are trained by 36 months (Boyse & Fitzgerald, 2010). The child’s age is not as important as his/her physical and emotional readiness. If started too early, it might take longer to train a child. If a child resists being trained, or it is not successful after a few weeks, it is best to take a break and try again later. Most children master daytime bladder control first, typically within two to three months of consistent toilet training. However, nap and nighttime training might take months or even years.

According to the Mayo Clinic (2016b) the following questions can help parents determine if a child is ready for toilet training:

Does your child seem interested in the potty chair or toilet, or in wearing underwear?

Can your child understand and follow basic directions?

Does your child complain about wet or dirty diapers?

Does your child tell you through words, facial expressions or posture when he or she needs to go?

Does your child stay dry for periods of two hours or longer during the day?

Can your child pull down his or her pants and pull them up again?

Can your child sit on and rise from a potty chair? (p. 1)

Some children experience elimination disorders that may require intervention by the child’s pediatrician or a trained mental health practitioner. Elimination disorders include: enuresis, or the repeated voiding of urine into bed or clothes (involuntary or intentional) and encopresis, the repeated passage of feces into inappropriate places (involuntary or intentional) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The prevalence of enuresis is 5%-10% for 5-year-olds, 3%-5% for 10-year-olds and approximately 1% for those 15 years of age or older. Around 1% of 5-year-olds have encopresis, and it is more common in males than females.

4.1.4 Sleep

During early childhood, there is wide variation in the number of hours of sleep recommended per day. For example, two-year-olds may still need 15-16 hours per day, while a six-year-old may only need 7-8 hours. The National Sleep Foundation’s 2015 recommendations based on age are listed in Figure 4.6.

4.1.5 Sexual Development in Early Childhood

Historically, children have been thought of as innocent or incapable of sexual arousal (Aries, 1962). Yet, the physical dimension of sexual arousal is present from birth. However, to associate the elements of seduction, power, love, or lust that is part of the adult meanings of sexuality would be inappropriate. Sexuality begins in childhood as a response to physical states and sensation and cannot be interpreted as similar to that of adults in any way (Carroll, 2007).

Infancy: Boys and girls are capable of erections and vaginal lubrication even before birth (Martinson, 1981). Arousal can signal overall physical contentment and stimulation that accompanies feeding or warmth. Infants begin to explore their bodies and touch their genitals as soon as they have the sufficient motor skills. This stimulation is for comfort or to relieve tension rather than to reach orgasm (Carroll, 2007).

Early Childhood: Self-stimulation is common in early childhood for both boys and girls. Curiosity about the body and about others’ bodies is a natural part of early childhood as well. As children grow, they are more likely to show their genitals to siblings or peers, and to take off their clothes and touch each other (Okami, Olmstead, & Abramson, 1997). Masturbation is common for both boys and girls. Boys are often shown by other boys how to masturbate, but girls tend to find out accidentally. Additionally, boys masturbate more often and touch themselves more openly than do girls (Schwartz, 1999).

Hopefully, parents respond to this without undue alarm and without making the child feel guilty about their bodies. Instead, messages about what is going on and the appropriate time and place for such activities help the child learn what is appropriate.

4.1.6 Nutritional Concerns

In addition to those in early childhood having a smaller appetite, their parents may notice a general reticence to try new foods, or a preference for certain foods, often served or eaten in a particular way. Some of these changes can be traced back to the “just right” (or just-so) phenomenon that is common in early childhood. Many young children desire consistency and may be upset if there are even slight changes to their daily routines. They may like to line up their toys or other objects or place them in symmetric patterns. They may arrange the objects until they feel “just right”. Many young children have a set bedtime ritual and a strong preference for certain clothes, toys or games. All these tendencies tend to wane as children approach middle childhood, and the familiarity of such ritualistic behaviors seem to bring a sense of security and general reduction in childhood fears and anxiety (Evans, Gray, & Leckman, 1999; Evans & Leckman, 2015).

Malnutrition due to insufficient food is not common in developed nations, like the United States, yet many children lack a balanced diet. Added sugars and solid fats contribute to 40% of daily calories for children and teens in the US. Approximately half of these empty calories come from six sources: soda, fruit drinks, dairy desserts, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk (CDC, 2015). Caregivers need to keep in mind that they are setting up taste preferences at this age. Young children who grow accustomed to high fat, very sweet and salty flavors may have trouble eating foods that have subtler flavors, such as fruits and vegetables. Consider the following advice (See Box 4.1) about establishing eating patterns for years to come (Rice, 1997). Notice that keeping mealtime pleasant, providing sound nutrition and not engaging in power struggles over food are the main goals:

Recognize that appetite varies. Children may eat well at one meal and have no appetite at another. Rather than seeing this as a problem, it may help to realize that appetites do vary. Continue to provide good nutrition, but do not worry excessively if the child does not eat at a particular meal.

Keep it pleasant. This tip is designed to help caregivers create a positive atmosphere during mealtime. Mealtimes should not be the time for arguments or expressing tensions. You do not want the child to have painful memories of mealtimes together or have nervous stomachs and problems eating and digesting food due to stress.

No short order chefs. While it is fine to prepare foods that children enjoy, preparing a different meal for each child or family member sets up an unrealistic expectation from others. Children probably do best when they are hungry, and a meal is ready. Limiting snacks rather than allowing children to “graze” can help create an appetite for what is being served.

Limit choices. If you give your young child choices, make sure that you give them one or two specific choices rather than asking “What would you like for lunch?” If given an open choice, children may change their minds or ask for something that is not available or appropriate.

Serve balanced meals. This tip encourages caregivers to serve balanced meals. A box of macaroni and cheese is not a balanced meal. Meals prepared at home tend to have better nutritional value than fast food or frozen dinners. Prepared foods tend to be higher in fat and sugar content, as these ingredients enhance taste and profit margin because fresh food is often costlier and less profitable. However, preparing fresh food at home is not costly. It does, however, require more activity. Preparing meals and including the children in kitchen chores can provide a fun and memorable experience.

Do not bribe. Bribing a child to eat vegetables by promising desert is not a good idea. The child will likely find a way to get the desert without eating the vegetables (by whining or fidgeting, perhaps, until the caregiver gives in). In addition, bribery teaches the child that some foods are better than others. Children tend to naturally enjoy a variety of foods until they are taught that some are considered less desirable than others. Most important is not to force your child to eat or fight over eating food.

4.2 Cognitive Development in Early Childhood

Describe Piaget’s preoperational stage and the characteristics of preoperational thought

Summarize the challenges to Piaget’s theory

Describe Vygotsky’s theory of cognitive development

Describe Information processing research on attention and memory

Describe the views of the neo-Piagetians

Describe theory-theory and the development of theory of mind

Describe the developmental changes in language

Describe the various types of early childhood education

Describe the characteristics of autism

Early childhood is a time of pretending, blending fact and fiction, and learning to think of the world using language. As young children move away from needing to touch, feel, and hear about the world, they begin learning basic principles about how the world works. Concepts such as tomorrow, time, size, distance and fact vs. fiction are not easy to grasp at this age, but these tasks are all part of cognitive development during early childhood.

4.2.1 Piaget’s Preoperational Stage

Piaget’s stage that coincides with early childhood is the preoperational stage. According to Piaget, this stage occurs from the age of 2 to 7 years. In the preoperational stage, children use symbols to represent words, images, and ideas, which is why children in this stage engage in pretend play. A child’s arms might become airplane wings as she zooms around the room, or a child with a stick might become a brave knight with a sword. Children also begin to use language in the preoperational stage, but they cannot understand adult logic or mentally manipulate information. The term operational refers to logical manipulation of information, so children at this stage are considered pre-operational. Children’s logic is based on their own personal knowledge of the world so far, rather than on conventional knowledge.

The preoperational period is divided into two stages: The symbolic function substage occurs between 2 and 4 years of age and is characterized by the child being able to mentally represent an object that is not present and a dependence on perception in problem solving. The intuitive thought substage, lasting from 4 to 7 years, is marked by greater dependence on intuitive thinking rather than just perception (Thomas, 1979). This implies that children think automatically without using evidence. At this stage, children ask many questions as they attempt to understand the world around them using immature reasoning. Let us examine some of Piaget’s assertions about children’s cognitive abilities at this age.

Pretend Play: Pretending is a favorite activity at this time. A toy has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything originally intended. A teddy bear, for example, can be a baby or the queen of a faraway land. Piaget believed that children’s pretend play helped children solidify new schemata they were developing cognitively. This play, then, reflected changes in their conceptions or thoughts. However, children also learn as they pretend and experiment. Their play does not simply represent what they have learned (Berk, 2007).

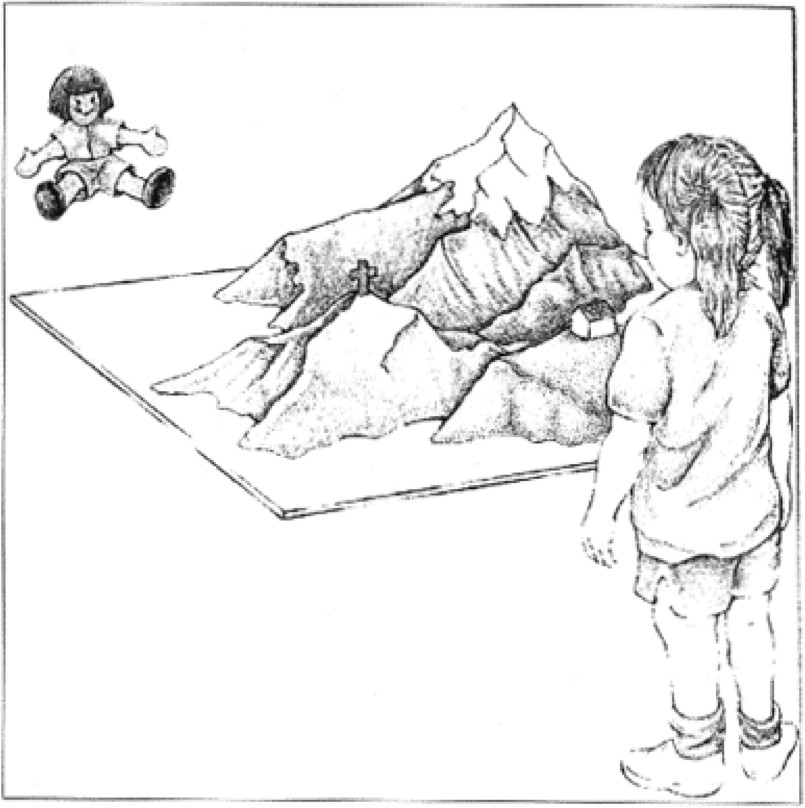

Egocentrism: Egocentrism in early childhood refers to the tendency of young children not to be able to take the perspective of others, and instead the child thinks that everyone sees, thinks, and feels just as they do. Egocentric children are not able to infer the perspective of other people and instead attribute their own perspective to situations. For example, ten-year-old Keiko’s birthday is coming up, so her mom takes 3-year-old Kenny to the toy store to choose a present for his sister. He selects an Iron Man action figure for her, thinking that if he likes the toy, his sister will too.

Piaget’s classic experiment on egocentrism involved showing children a three-dimensional model of a mountain and asking them to describe what a doll that is looking at the mountain from a different angle might see (see Figure 4.9). Children tend to choose a picture that represents their own, rather than the doll’s view. By age 7 children are less self-centered. However, even younger children when speaking to others tend to use different sentence structures and vocabulary when addressing a younger child or an older adult. This indicates some awareness of the views of others.

Conservation Errors: Conservation refers to the ability to recognize that moving or rearranging matter does not change the quantity. Using Kenny and Keiko again, dad gave a slice of pizza to 10-year-old Keiko and another slice to 3-year-old Kenny. Kenny’s pizza slice was cut into five pieces, so Kenny told his sister that he got more pizza than she did. Kenny did not understand that cutting the pizza into smaller pieces did not increase the overall amount. This was because Kenny exhibited centration or focused on only one characteristic of an object to the exclusion of others. Kenny focused on the five pieces of pizza to his sister’s one piece even though the total amount was the same. Keiko was able to consider several characteristics of an object than just one. Because children have not developed this understanding of conservation, they cannot perform mental operations.

The classic Piagetian experiment associated with conservation involves liquid (Crain, 2005). As seen in Figure 4.10, the child is shown two glasses (as shown in a) which are filled to the same level and asked if they have the same amount. Usually the child agrees they have the same amount. The experimenter then pours the liquid in one glass to a taller and thinner glass (as shown in b). The child is again asked if the two glasses have the same amount of liquid. The preoperational child will typically say the taller glass now has more liquid because it is taller (as shown in c). The child has centrated on the height of the glass and fails to conserve.

Classification Errors: Preoperational children have difficulty understanding that an object can be classified in more than one way. For example, if shown three white buttons and four black buttons and asked whether there are more black buttons or buttons, the child is likely to respond that there are more black buttons. They do not consider the general class of buttons. Because young children lack these general classes, their reasoning is typically transductive, that is, making faulty inferences from one specific example to another. For example, Piaget’s daughter Lucienne stated she had not had her nap, therefore it was not afternoon. She did not understand that afternoons are a time period and her nap was just one of many events that occurred in the afternoon (Crain, 2005). As the child’s vocabulary improves and more schemata are developed, the ability to classify objects improves.

Animism: Animism refers to attributing life-like qualities to objects. The cup is alive, the chair that falls down and hits the child’s ankle is mean, and the toys need to stay home because they are tired. Cartoons frequently show objects that appear alive and take on lifelike qualities. Young children do seem to think that objects that move may be alive, but after age three, they seldom refer to objects as being alive (Berk, 2007).

Critique of Piaget: Similar to the critique of the sensorimotor period, several psychologists have attempted to show that Piaget also underestimated the intellectual capabilities of the preoperational child. For example, children’s specific experiences can influence when they are able to conserve. Children of pottery makers in Mexican villages know that reshaping clay does not change the amount of clay at much younger ages than children who do not have similar experiences (Price-Williams, Gordon, & Ramirez, 1969). Crain (2005) indicated that preoperational children can think rationally on mathematical and scientific tasks, and they are not as egocentric as Piaget implied. Research on Theory of Mind (discussed later in the chapter) has demonstrated that children overcome egocentrism by 4 or 5 years of age, which is sooner than Piaget indicated.

4.2.2 Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development

Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) was a Russian psychologist who argued that culture has a major impact on a child’s cognitive development. Piaget and Gesell believed development stemmed directly from the child, and although Vygotsky acknowledged intrinsic development, he argued that it is the language, writings, and concepts arising from the culture that elicit the highest level of cognitive thinking (Crain, 2005). He believed that the social interactions with adults and more learned peers can facilitate a child’s potential for learning. Without this interpersonal instruction, he believed children’s minds would not advance very far as their knowledge would be based only on their own discoveries. Some of Vygotsky’s key concepts are described below.

Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding: Vygotsky’s best-known concept is the zone of proximal development (ZPD). Vygotsky stated that children should be taught in the ZPD, which occurs when they can almost perform a task, but not quite on their own without assistance. With the right kind of teaching, however, they can accomplish it successfully. A good teacher identifies a child’s ZPD and helps the child stretch beyond it. Then the adult (teacher) gradually withdraws support until the child can then perform the task unaided. Researchers have applied the metaphor of scaffolds (the temporary platforms on which construction workers stand) to this way of teaching. Scaffolding is the temporary support that parents or teachers give a child to do a task.

Private Speech: Do you ever talk to yourself? Why? Chances are, this occurs when you are struggling with a problem, trying to remember something, or feel very emotional about a situation. Children talk to themselves too. Piaget interpreted this as egocentric speech or speech that is focused on the child and does not include another’s point of view.

Vygotsky, however, believed that children talk to themselves in order to solve problems or clarify thoughts. As children learn to think in words, they do so aloud before eventually closing their lips and engaging in private speech or inner speech.

Thinking out loud eventually becomes thought accompanied by internal speech and talking to oneself becomes a practice only engaged in when we are trying to learn something or remember something. This inner speech is not as elaborate as the speech we use when communicating with others (Vygotsky, 1962).

Contrast with Piaget: Piaget was highly critical of teacher-directed instruction believing that teachers who take control of the child’s learning place the child into a passive role (Crain, 2005). Further, teachers may present abstract ideas without the child’s true understanding, and instead they just repeat back what they heard. Piaget believed children must be given opportunities to discover concepts on their own. As previously stated, Vygotsky did not believe children could reach a higher cognitive level without instruction from more learned individuals. Who is correct? Both theories certainly contribute to our understanding of how children learn.

4.2.3 Information Processing

Information processing researchers have focused on several issues in cognitive development for this age group, including improvements in attention skills, changes in the capacity and the emergence of executive functions in working memory. Additionally, in early childhood memory strategies, memory accuracy, and autobiographical memory emerge. Early childhood is seen by many researchers as a crucial time period in memory development (Posner & Rothbart, 2007).

4.2.4 Attention

Changes in attention have been described by many as the key to changes in human memory (Nelson & Fivush, 2004; Posner & Rothbart, 2007). However, attention is not a unified function; it is comprised of sub-processes. The ability to switch our focus between tasks or external stimuli is called divided attention or multitasking. This is separate from our ability to focus on a single task or stimulus, while ignoring distracting information, called selective attention. Different from these is sustained attention, or the ability to stay on task for long periods of time. Moreover, we also have attention processes that influence our behavior and enable us to inhibit a habitual or dominant response, and others that enable us to distract ourselves when upset or frustrated.

Divided Attention: Young children (age 3-4) have considerable difficulties in dividing their attention between two tasks, and often perform at levels equivalent to our closest relative, the chimpanzee, but by age five they have surpassed the chimp (Hermann, Misch, Hernandez-Lloreda & Tomasello, 2015; Hermann & Tomasello, 2015). Despite these improvements, 5-year-olds continue to perform below the level of school-age children, adolescents, and adults.

Selective Attention: Children’s ability with selective attention tasks improve as they age. However, this ability is also greatly influenced by the child’s temperament (Rothbart & Rueda, 2005), the complexity of the stimulus or task (Porporino, Shore, Iarocci & Burack, 2004), and along with whether the stimuli are visual or auditory (Guy, Rogers & Cornish, 2013). Guy et al. found that children’s ability to selectively attend to visual information outpaced that of auditory stimuli. This may explain why young children are not able to hear the voice of the teacher over the cacophony of sounds in the typical preschool classroom (Jones, Moore & Amitay, 2015). Jones and his colleagues found that 4 to 7-year-olds could not filter out background noise, especially when its frequencies were close in sound to the target sound. In comparison, 8 to 11-year-old older children often performed similar to adults.

Sustained Attention: Most measures of sustained attention typically ask children to spend several minutes focusing on one task, while waiting for an infrequent event, while there are multiple distractors for several minutes. Berwid, Curko-Kera, Marks and Halperin (2005) asked children between the ages of 3 and 7 to push a button whenever a “target” image was displayed, but they had to refrain from pushing the button when a non-target image was shown. The younger the child, the more difficulty he or she had maintaining their attention.

4.2.5 Memory

Based on studies of adults, people with amnesia, and neurological research on memory, researchers have proposed several “types” of memory (see Figure 4.14). Sensory memory (also called the sensory register) is the first stage of the memory system, and it stores sensory input in its raw form for a very brief duration; essentially long enough for the brain to register and start processing the information. Studies of auditory sensory memory have found that the sensory memory trace for the characteristics of a tone last about one second in 2-year-olds, two seconds in 3-year-olds, more than two seconds in 4-year-olds and three to five seconds in 6-year-olds (Glass, Sachse, & vob Suchodoletz, 2008). Other researchers have found that young children hold sounds for a shorter duration than do older children and adults, and that this deficit is not due to attentional differences between these age groups but reflect differences in the performance of the sensory memory system (Gomes et al., 1999).

The second stage of the memory system is called short-term or working memory. Working memory is the component of memory in which current conscious mental activity occurs. Working memory often requires conscious effort and adequate use of attention to function effectively. As you read earlier, children in this age group struggle with many aspects of attention, and this greatly diminishes their ability to consciously juggle several pieces of information in memory. The capacity of working memory, that is the amount of information someone can hold in consciousness, is smaller in young children than in older children and adults (Galotti, 2018). The typical adult and teenager can hold a 7-digit number active in their short-term memory. The typical 5-year-old can hold only a 4-digit number active. This means that the more complex a mental task is, the less efficient a younger child will be in paying attention to, and actively processing, information in order to complete the task.

Changes in attention and the working memory system also involve changes in executive function. Executive function (EF) refers to self-regulatory processes, such as the ability to inhibit a behavior or cognitive flexibility, that enable adaptive responses to new situations or to reach a specific goal. Executive function skills gradually emerge during early childhood and continue to develop throughout childhood and adolescence. Like many cognitive changes, brain maturation, especially the prefrontal cortex, along with experience influence the development of executive function skills. Children show higher executive function skills when parents are warm and responsive, use scaffolding when the child is trying to solve a problem, and provide cognitively stimulating environments (Fay-Stammbach, Hawes & Meredith, 2014). For instance, scaffolding was positively correlated with greater cognitive flexibility at age two and inhibitory control at age four (Bibok, Carpendale & Müller, 2009).

Older children and adults use mental strategies to aid their memory performance. For instance, simple rote rehearsal may be used to commit information to memory. Young children often do not rehearse unless reminded to do so, and when they do rehearse, they often fail to use clustering rehearsal. In clustering rehearsal, the person rehearses previous material while adding in additional information. If a list of words is read out loud to you, you are likely to rehearse each word as you hear it along with any previous words you were given. Young children will repeat each word they hear, but often fail to repeat the prior words in the list. In Schneider, Kron-Sperl and Hunnerkopf’s (2009) longitudinal study of 102 kindergarten children, the majority of children used no strategy to remember information, a finding that was consistent with previous research. As a result, their memory performance was poor when compared to their abilities as they aged and started to use more effective memory strategies.

The third component in memory is long-term memory, which is also known as permanent memory. A basic division of long-term memory is between declarative and non-declarative memory. Declarative memories, sometimes referred to as explicit memories, are memories for facts or events that we can consciously recollect. Non-declarative memories, sometimes referred to as implicit memories, are typically automated skills that do not require conscious recollection. Remembering that you have an exam next week would be an example of a declarative memory. In contrast, knowing how to walk so you can get to the classroom or how to hold a pencil to write would be examples of non-declarative memories. Declarative memory is further divided into semantic and episodic memory. Semantic memories are memories for facts and knowledge that are not tied to a timeline, while episodic memories are tied to specific events in time.

A component of episodic memory is autobiographical memory, or our personal narrative. As you may recall in Chapter 3, the concept of infantile amnesia was introduced. Adults rarely remember events from the first few years of life. In other words, we lack autobiographical memories from our experiences as an infant, toddler and very young preschooler. Several factors contribute to the emergence of autobiographical memory, including brain maturation, improvements in language, opportunities to talk about experiences with parents and others, the development of theory of mind, and a representation of “self” (Nelson & Fivush, 2004). Two-year-olds do remember fragments of personal experiences, but these are rarely coherent accounts of past events (Nelson & Ross, 1980). Between 2 and 2 ½ years of age children can provide more information about past experiences. However, these recollections require considerable prodding by adults (Nelson & Fivush, 2004). Over the next few years, children will form more detailed autobiographical memories and engage in more reflection of the past.

4.2.6 Neo-Piagetians

As previously discussed, Piaget’s theory has been criticized on many fronts, and updates to reflect more current research have been provided by the Neo-Piagetians, or those theorists who provide “new” interpretations of Piaget’s theory. Morra, Gobbo, Marini and Sheese (2008) reviewed Neo-Piagetian theories, which were first presented in the 1970s, and identified how these “new” theories combined Piagetian concepts with those found in Information Processing. Similar to Piaget’s theory, Neo-Piagetian theories believe in constructivism, assume cognitive development can be separated into different stages with qualitatively different characteristics, and advocate that children’s thinking becomes more complex in advanced stages. Unlike Piaget, Neo-Piagetians believe that aspects of information processing change the complexity of each stage, not logic as determined by Piaget.

Neo-Piagetians propose that working memory capacity is affected by biological maturation, and therefore restricts young children’s ability to acquire complex thinking and reasoning skills. Increases in working memory performance and cognitive skills development coincide with the timing of several neurodevelopmental processes. These include myelination, axonal and synaptic pruning, changes in cerebral metabolism, and changes in brain activity (Morra et al., 2008). Myelination especially occurs in waves between birth and adolescence, and the degree of myelination in particular areas explains the increasing efficiency of certain skills. Therefore, brain maturation, which occurs in spurts, affects how and when cognitive skills develop. Additionally, all Neo-Piagetian theories support that experience and learning interact with biological maturation in shaping cognitive development. 131

4.2.7 Children’s Understanding of the World

Both Piaget and Vygotsky believed that children actively try to understand the world around them, referred to as constructivism. However, Piaget is identified as a cognitive constructivitst, which focuses on independent learning, while Vygotsky is a social constrctivist relying on social interactions for learning. More recently developmentalists have added to this understanding by examining how children organize information and develop their own theories about the world.

Theory-Theory is the tendency of children to generate theories to explain everything they encounter. This concept implies that humans are naturally inclined to find reasons and generate explanations for why things occur. Children frequently ask question about what they see or hear around them. When the answers provided do not satisfy their curiosity or are too complicated for them to understand, they generate their own theories. In much the same way that scientists construct and revise their theories, children do the same with their intuitions about the world as they encounter new experiences (Gopnik & Wellman, 2012). One of the theories they start to generate in early childhood centers on the mental states; both their own and those of others.

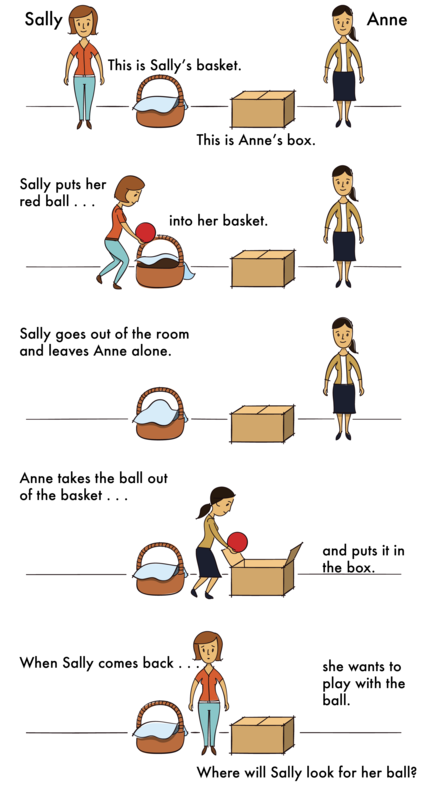

Theory of mind refers to the ability to think about other people’s thoughts. This mental mind reading helps humans to understand and predict the reactions of others, thus playing a crucial role in social development. One common method for determining if a child has reached this mental milestone is the false belief task. The research began with a clever experiment by Wimmer and Perner (1983), who tested whether children can pass a false-belief test (see Figure 4.17). The child is shown a picture story of Sally, who puts her ball in a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is out of the room, Anne comes along and takes the ball from the basket and puts it inside a box. The child is then asked where Sally thinks the ball is located when she comes back to the room. Is she going to look first in the box or in the basket? The right answer is that she will look in the basket, because that is where she put it and thinks it is; but we have to infer this false belief against our own better knowledge that the ball is in the box. This is very difficult for children before the age of four because of the cognitive effort it takes. Three-year-olds have difficulty distinguishing between what they once thought was true and what they now know to be true. They feel confident that what they know now is what they have always known (Birch & Bloom, 2003). Even adults need to think through this task (Epley, Morewedge, & Keysar, 2004). To be successful at solving this type of task the child must separate what he or she “knows” to be true from what someone else might “think” is true.

In Piagetian terms, children must give up a tendency toward egocentrism. The child must also understand that what guides people’s actions and responses are what they believe rather than what is reality. In other words, people can mistakenly believe things that are false and will act based on this false knowledge. Consequently, prior to age four children are rarely successful at solving such a task (Wellman, Cross & Watson, 2001).

Researchers examining the development of theory of mind have been concerned by the overemphasis on the mastery of false belief as the primary measure of whether a child has attained theory of mind. Two-year-olds understand the diversity of desires, yet as noted earlier it is not until age four or five that children grasp false belief, and often not until middle childhood do they understand that people may hide how they really feel. In part, because children in early childhood have difficulty hiding how they really feel. Wellman and his colleagues (Wellman, Fang, Liu, Zhu & Liu, 2006) suggest that theory of mind is comprised of a number of components, each with its own developmental timeline (see Table 4.2).

Those in early childhood in the US, Australia, and Germany develop theory of mind in the sequence outlined in Table 4.2. Yet, Chinese and Iranian preschoolers acquire knowledge access before diverse beliefs (Shahaeian, Peterson, Slaughter & Wellman, 2011). Shahaeian and colleagues suggested that cultural differences in child-rearing may account for this reversal. Parents in collectivistic cultures, such as China and Iran, emphasize conformity to the family and cultural values, greater respect for elders, and the acquisition of knowledge and academic skills more than they do autonomy and social skills (Frank, Plunkett & Otten, 2010). This could reduce the degree of familial conflict of opinions expressed in the family. In contrast, individualistic cultures encourage children to think for themselves and assert their own opinion, and this could increase the risk of conflict in beliefs being expressed by family members. As a result, children in individualistic cultures would acquire insight into the question of diversity of belief earlier, while children in collectivistic cultures would acquire knowledge access earlier in the sequence. The role of conflict in aiding the development of theory of mind may account for the earlier age of onset of an understanding of false belief in children with siblings, especially older siblings (McAlister & Petersen, 2007; Perner, Ruffman & Leekman, 1994).

| Component | Description |

| Diverse-desires | Understanding that two people may have different desires regarding the same object. |

| Diverse-beliefs | Understanding that two people may hold different beliefs about an object. |

| Knowledge access (knowledge/ignorance) | Understanding that people may or may not have access to information. |

| False belief | Understanding that someone might hold a belief based on false information. |

4.2.8 Language Development

Vocabulary growth: A child’s vocabulary expands between the ages of two to six from about 200 words to over 10,000 words. This “vocabulary spurt” typically involves 10-20 new words per week and is accomplished through a process called fast-mapping. Words are easily learned by making connections between new words and concepts already known. The parts of speech that are learned depend on the language and what is emphasized. Children speaking verb-friendly languages, such as Chinese and Japanese, learn verbs more readily, while those speaking English tend to learn nouns more readily. However, those learning less verb-friendly languages, such as English, seem to need assistance in grammar to master the use of verbs (Imai et al., 2008).

Literal meanings: Children can repeat words and phrases after having heard them only once or twice, but they do not always understand the meaning of the words or phrases. This is especially true of expressions or figures of speech which are taken literally. For example, a classroom full of preschoolers hears the teacher say, “Wow! That was a piece of cake!” The children began asking “Cake? Where is my cake? I want cake!”

Overregularization: Children learn rules of grammar as they learn language but may apply these rules inappropriately at first. For instance, a child learns to add “ed” to the end of a word to indicate past tense. Then form a sentence such as “I goed there. I doed that.” This is typical at ages two and three. They will soon learn new words such as “went” and “did” to be used in those situations.

The impact of training: Remember Vygotsky and the Zone of Proximal Development? Children can be assisted in learning language by others who listen attentively, model more accurate pronunciations and encourage elaboration. The child exclaims, “I’m goed there!” and the adult responds, “You went there? Say, ‘I went there.’ Where did you go?” Children may be ripe for language as Chomsky suggests, but active participation in helping them learn is important for language development as well. The process of scaffolding is one in which the guide provides needed assistance to the child as a new skill is learned.

4.2.9 Bilingualism

Although monolingual speakers often do not realize it, the majority of children around the world are Bilingual, meaning that they understand and use two languages (Meyers-Sutton, 2005). Even in the United States, which is a relatively monolingual society, more than 60 million people (21%) speak a language other than English at home (Camarota & Zeigler, 2014; Ryan, 2013). Children who are dual language learners are one of the fastest growing populations in the United States (Hammer et al., 2014). They make up nearly 30% of children enrolled in early childhood programs, like Head Start. By the time they enter school, they are very heterogeneous in their language and literacy skills, with some children showing delays in being proficient in either one or both languages (Hammer et al., 2014). Hoff (2018) reports language competency is dependent on the quantity, quality, and opportunity to use a language. Dual language learners may hear the same number of words and phrases (quantity) overall, as do monolingual children, but it is split between two languages (Hoff, 2018). Thus, in any single language they may be exposed to fewer words. They will show higher expressive and receptive skills in the language they come to hear the most.

In addition, the quality of the languages spoken to the child may differ in bilingual versus monolingual families. Place and Hoff (2016) found that for many immigrant children in the United States, most of the English heard was spoken by a non-native speaker of the language. Finally, many children in bilingual households will sometimes avoid using the family’s heritage language in favor of the majority language (DeHouwer, 2007, Hoff, 2018). A common pattern in Spanish-English homes, is for the parents to speak to the child in Spanish, but for the child to respond in English. As a result, children may show little difference in the receptive skills between English and Spanish, but better expressive skills in English (Hoff, 2018).

There are several studies that have documented the advantages of learning more than one language in childhood for cognitive executive function skills. Bilingual children consistently outperform monolinguals on measures of inhibitory control, such as ignoring irrelevant information (Bialystok, Martin & Viswanathan, 2005). Studies also reveal an advantage for bilingual children on measures of verbal working memory (Kaushanskaya, Gross, & Buac, 2014; Yoo & Kaushanskaya, 2012) and non-verbal working memory (Bialystok, 2011). However, it has been reported that among lower SES populations the working memory advantage is not always found (Bonifacci, Giombini, Beloocchi, & Conteno, 2011).

There is also considerable research to show that being bilingual, either as a child or an adult, leads to greater efficiency in the word learning process. Monolingual children are strongly influenced by the mutual-exclusivity bias, the assumption that an object has only a single name (Kaushanskaya, Gross, & Buac, 2014). For example, a child who has previously learned the word car, may be confused when this object is referred to as an automobile or sedan. Research shows that monolingual children find it easier to learn the name of a new object, than acquiring a new name for a previously labelled object. In contrast, bilingual children and adults show little difficulty with either task (Kaushanskaya & Marian, 2009). This finding may be explained by the experience bilinguals have in translating between languages when referring to familiar objects.

4.2.10 Preschool

Providing universal preschool has become an important lobbying point for federal, state, and local leaders throughout our country. In his 2013 State of the Union address, President Obama called upon congress to provide high quality preschool for all children. He continued to support universal preschool in his legislative agenda, and in December 2014 the President convened state and local policymakers for the White House Summit on Early Education (White House Press Secretary, 2014). However, universal preschool covering all four-year olds in the country would require significant funding. Further, how effective preschools are in preparing children for elementary school, and what constitutes high quality preschool have been debated.

To set criteria for designation as a high-quality preschool, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) identifies 10 standards (NAEYC, 2016). These include:

Positive relationships among all children and adults are promoted.

A curriculum that supports learning and development in social, emotional, physical, language, and cognitive areas.

Teaching approaches that are developmentally, culturally and linguistically appropriate.

Assessment of children’s progress to provide information on learning and development.

The health and nutrition of children are promoted, while they are protected from illness and injury.

Teachers possess the educational qualifications, knowledge, and commitment to promote children’s learning.

Collaborative relationships with families are established and maintained.

Relationships with agencies and institutions in the children’s communities are established to support the program’s goals.

The indoor and outdoor physical environments are safe and well-maintained.

Leadership and management personnel are well qualified, effective, and maintain licensure status with the applicable state agency.

Parents should review preschool programs using the NAEYC criteria as a guide and template for asking questions that will assist them in choosing the best program for their child. Selecting the right preschool is also difficult because there are so many types of preschools available. Zachry (2013) identified Montessori, Waldorf, Reggio Emilia, High Scope, Parent Co-Ops and Bank Street as types of preschool programs that focus on children learning through discovery. Teachers act as guides and create activities based on the child’s developmental level. 136

Head Start: For children who live in poverty, Head Start has been providing preschool education since 1965 when it was begun by President Lyndon Johnson as part of his war on poverty. It currently serves nearly one million children and annually costs approximately 7.5 billion dollars (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). However, concerns about the effectiveness of Head Start have been ongoing since the program began. Armor (2015) reviewed existing research on Head Start and found there were no lasting gains, and the average child in Head Start had not learned more than children who did not receive preschool education.

A 2015 report evaluating the effectiveness of Head Start comes from the What Works Clearinghouse. The What Works Clearinghouse identifies research that provides reliable evidence of the effectiveness of programs and practices in education and is managed by the Institute of Education Services for the United States Department of Education. After reviewing 90 studies on the effectiveness of Head Start, only one study was deemed scientifically acceptable and this study showed disappointing results (Barshay, 2015). This study showed that 3-and 4-year-old children in Head Start received “potentially positive effects” on general reading achievement, but no noticeable effects on math achievement and social-emotional development.

Nonexperimental designs are a significant problem in determining the effectiveness of Head Start programs because a control group is needed to show group differences that would demonstrate educational benefits. Because of ethical reasons, low income children are usually provided with some type of pre-school programming in an alternative setting. Additionally, head Start programs are different depending on the location, and these differences include the length of the day or qualification of the teachers. Lastly, testing young children is difficult and strongly dependent on their language skills and comfort level with an evaluator (Barshay, 2015).

4.2.11 Autism Spectrum Disorder

A greater discussion on disorders affecting children and special educational services to assist them will occur in Chapter 5. However, because characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder must be present in the early developmental period, as established by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013), this disorder will be presented here. So, what exactly is an Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Autism spectrum disorder is probably the most misunderstood and puzzling of the neurodevelopmental disorders. Children with this disorder show signs of significant disturbances in three main areas: (a) deficits in social interaction, (b) deficits in communication, and (c) repetitive patterns of behavior or interests. These disturbances appear early in life and cause serious impairments in functioning (APA, 2013). The child with autism spectrum disorder might exhibit deficits in social interaction by not initiating conversations with other children or turning their head away when spoken to. These children do not make eye contact with others and seem to prefer playing alone rather than with others. In a certain sense, it is almost as though these individuals live in a personal and isolated social world which others are simply not privy to or able to penetrate. Communication deficits can range from a complete lack of speech, to one-word responses (e.g., saying “Yes” or “No” when replying to questions or statements that require additional elaboration), to echoed speech (e.g., parroting what another person says, either immediately or several hours or even days later), and to difficulty maintaining a conversation because of an inability to reciprocate others’ comments. These deficits can also include problems in using and understanding nonverbal cues (e.g., facial expressions, gestures, and postures) that facilitate normal communication.

Repetitive patterns of behavior or interests can be exhibited a number of ways. The child might engage in stereotyped, repetitive movements (rocking, head-banging, or repeatedly dropping an object and then picking it up), or she might show great distress at small changes in routine or the environment. For example, the child might throw a temper tantrum if an object is not in its proper place or if a regularly-scheduled activity is rescheduled. In some cases, the person with autism spectrum disorder might show highly restricted and fixated interests that appear to be abnormal in their intensity. For instance, the child might learn and memorize every detail about something even though doing so serves no apparent purpose. Importantly, autism spectrum disorder is not the same thing as intellectual disability, although these two conditions can occur together. The DSM-5 specifies that the symptoms of autism spectrum disorder are not caused or explained by intellectual disability.

The qualifier “spectrum” in autism spectrum disorder is used to indicate that individuals with the disorder can show a range, or spectrum, of symptoms that vary in their magnitude and severity: Some severe, others less severe. The previous edition of the DSM included a diagnosis of Asperger’s disorder, generally recognized as a less severe form of autistim spectrum disorder. Individuals diagnosed with Asperger’s disorder were described as having average or high intelligence and a strong vocabulary, but exhibiting impairments in social interaction and social communication, such as talking only about their special interests (Wing, Gould, & Gillberg, 2011). However, because research has failed to demonstrate that Asperger’s disorder differs from autism spectrum disorder, the DSM-5 does not include it. Some individuals with autism spectrum disorder, particularly those with better language and intellectual skills, can live and work independently as adults. However, most do not because the symptoms cause serious impairment in many aspects of life (APA, 2013).

To determine current prevalence rates, the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network provides estimates of the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders among 8- year-old children who reside within 11 ADM sites in the United States, including Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Wisconsin (Baio et al., 2018). For 2014 (most recent data), estimates indicated that nearly 1 in 59 children in the United States has autism spectrum disorder, and the disorder is 4 times more common in boys (1 out of 38) than girls (1 out of 152).

Rates of autistim spectrum disorder have increased dramatically since the 1980s. For example, California saw an increase of 273% in reported cases from 1987 through 1998 (Byrd, 2002). Between 2000 and 2008, the rate of autism diagnoses in the United States increased 78% (CDC, 2012) and between 2000 and 2014 the rate increased 150% (Baio et al., 2018). Although it is difficult to interpret this increase, it is possible that the rise in prevalence is the result of the broadening of the diagnosis, increased efforts to identify cases in the community, and greater awareness and acceptance of the diagnosis. In addition, mental health professionals are now more knowledgeable about autism spectrum disorder and are better equipped to make the diagnosis, even in subtle cases (Novella, 2008).

The exact causes of autism spectrum disorder remain unknown despite massive research efforts over the last two decades (Meek, Lemery-Chalfant, Jahromi, & Valiente, 2013). Autism appears to be strongly influenced by genetics, as identical twins show concordance rates of 60%–90%, whereas concordance rates for fraternal twins and siblings are 5%–10% (Autism Genome Project Consortium, 2007). Many different genes and gene mutations have been implicated in autism (Meek et al., 2013). Among the genes involved are those important in the formation of synaptic circuits that facilitate communication between different areas of the brain (Gauthier et al., 2011). A number of environmental factors are also thought to be associated with increased risk for autism spectrum disorder, at least in part, because they contribute to new mutations. These factors include exposure to pollutants, such as plant emissions and mercury, urban versus rural residence, and vitamin D deficiency (Kinney, Barch, Chayka, Napoleon, & Munir, 2009).

A recent Swedish study looking at the records of over one million children born between 1973 and 2014 found that exposure to prenatal infections increased the risk for autism spectrum disorders (al-Haddad et al., 2019). Children born to mothers with an infection during pregnancy has a 79% increased risk of autism. Infections included: sepsis, flu, pneumonia, meningitis, encephalitis, an infection of the placental tissues or kidneys, or a urinary tract infection. One possible reason for the autism diagnosis is that the fetal brain is extremely vulnerable to damage from infections and inflammation. These results highlighted the importance of pregnant women receiving a flu vaccination and avoiding any infections during pregnancy.

There is no scientific evidence that a link exists between autism and vaccinations (Hughes, 2007). Indeed, a recent study compared the vaccination histories of 256 children with autism spectrum disorder with that of 752 control children across three time periods during their first two years of life (birth to 3 months, birth to 7 months, and birth to 2 years) (DeStefano, Price, & Weintraub, 2013). At the time of the study, the children were between 6 and 13 years old, and their prior vaccination records were obtained. Because vaccines contain immunogens (substances that fight infections), the investigators examined medical records to see how many immunogens children received to determine if those children who received more immunogens were at greater risk for developing autism spectrum disorder. The results of this study clearly demonstrated that the quantity of immunogens from vaccines received during the first two years of life were not at all related to the development of autism spectrum disorder.

4.4 References

Abuhatoum, S., & Howe, N. (2013). Power in sibling conflict during early and middle childhood. Social Development, 22, 738-754.

Al-Haddad, B., Jacobsson, B., Chabra, S., Modzelewska, D., Olson, E……. Sengpiel, V. (2019). Long-term risk of neuropsychiatric disease after exposure to infection in utero. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(6), 594-602.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2015). Gender identity development in children. Retrieved from https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/ gradeschool/Pages/Gender-Identity-and-Gender-Confusion-In-Children.aspx

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2016). Media and young minds. Retrieved from https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/138/5/e20162591

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychological Association. (2019). Immigration. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/advocacy/immigration 156

Ariès, P. (1962). Centuries of childhood: A social history of family life. New York: Knopf.

Armor, D. J. (2015). Head Start or false start. USA Today Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.questia.com/magazine/1G1-429736352/head-start-or-false-start

Autism Genome Project Consortium. (2007). Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nature Genetics, 39, 319–328.

Baio, J., Wiggins, L., Christensen, D., Maenner, M., ……. Dowling, N. (2018). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years-autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveillance Summary, 67(No. SS-6), 1-23. doi: http://dx.doi.org/a0.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1External

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Barshay, J. (2015). Report: Scant scientific evidence for Head Start programs’ effectiveness. U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved from http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/ 2015/08/03/report-scant-scientific-evidence-for-head-start-programs-effectiveness

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 4(1), part 2.

Baumrind, D. (2013). Authoritative parenting revisited: History and current status. In R. E. Larzelere, A. Sheffield, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.). Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 11-34). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88, 354-364.

Berk, L. E. (2007). Development through the life span (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Berwid, O., Curko-Kera, E. A., Marks, D. J., & Halperin, J. M. (2005). Sustained attention and response inhibition in young children at risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(11), 1219-1229.

Bialystok, E. (2011). Coordination of executive functions in monolingual and bilingual children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 110, 461–468.

Bialystok, E., Martin, M.M., & Viswanathan, M. (2005). Bilingualism across the lifespan: The rise and fall of inhibitory control. International Journal of Bilingualism, 9, 103–119.

Bibok, M.B., Carpendale, J.I.M., & Muller, U. (2009). Parental scaffolding and the development of executive function. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 123, 17-34.

Bigler, R. S., & Liben, L. S. (2007). Developmental intergroup theory: Exploring and reducing children’s social stereotyping and prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 162-166.

Birch, S., & Bloom, P. (2003). Children are cursed: An asymmetric bias in mental-state attribution. Psychological Science, 14(3), 283-286.

Blackless, M., Charuvastra, A., Derryck, A., Fausto-Sterling, A., Lauzanne, K., & Lee, E. (2000). How sexually dimorphic are we? Review and synthesis. American Journal of Human Biology, 12, 151-166.

Bonifacci, P., Giombini, L., Beloocchi, S., & Conteno, S. (2011). Speed of processing, anticipation, inhibition and working memory in bilinguals. Developmental Science, 14, 256–269.

Boyse, K. & Fitgerald, K. (2010). Toilet training. University of Michigan Health System. Retrieved from http://www.med.umich.edu/yourchild/topics/toilet.htm

Brody, G. H., Stoneman, Z., & McCoy, J. K. (1994). Forecasting sibling relationships in early adolescence from child temperament and family processes in middle childhood. Child development, 65, 771-784. 157

Brown, G.L., Mangelsdork, S.C., Agathen, J.M., & Ho, M. (2008). Young children’s psychological selves: Convergence with maternal reports of child personality. Social Development, 17, 161-182.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019). Employment characteristics of families-2018. Retrieved from

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/famee.pdf

Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review, 106(4), 676-713.

Byrd, R. (2002). Report to the legislature on the principal findings from the epidemiology of autism in California: A comprehensive pilot study. Retrieved from http://www.dds.ca.gov/Autism/MindReport.cfm

Camarota, S. A., & Zeigler, K. (2015). One in five U. S. residents speaks foreign language at home. Retrieved from https://cis.org/sites/default/files/camarota-language-15.pdf

Carroll, J. L. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2000). 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_11/sr11_246.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders, autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries, 61(3), 1–19. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6103.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Nutrition and health of young people. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/nutrition/facts.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). About adverse childhood experiences. Retrived from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/aboutace.html

Chang, A., Sandhofer, C., & Brown, C. S. (2011). Gender biases in early number exposure to preschool-aged children. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 30(4), 440-450.

Chiong, C., & Shuler, C. (2010). Learning: Is there an app for that? Investigations of young children’s usage and learning with mobile devices and apps. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. Retrieved from: https://clalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/files/learningapps_final_110410.pdf

Christakis, D.A. (2009). The effects of infant media usage: What do we know and what should we learn? Acta Paediatrica, 98, 8–16.

Clark, J. (1994). Motor development. In V. S. Ramachandran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (pp. 245–255). San Diego: Academic Press.

Colwell, M.J., & Lindsey, E.W. (2003). Teacher-child interactions and preschool children’s perceptions of self and peers. Early Childhood Development & Care, 173, 249-258.

Coté, C. A., & Golbeck, S. (2007). Preschoolers’ feature placement on own and others’ person drawings. International Journal of Early Years Education, 15(3), 231-243.

Courage, M.L., Murphy, A.N., & Goulding, S. (2010). When the television is on: The impact of infant-directed video on 6- and 18-month-olds’ attention during toy play and on parent-infant interaction. Infant Behavior and Development, 33, 176-188.

Crain, W. (2005). Theories of development concepts and applications (5th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

De Houwer, A. (2007). Parental language input patterns and children’s bilingual use. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 411–422

DeStefano, F., Price, C. S., & Weintraub, E. S. (2013). Increasing exposures to antibody-stimulating proteins and polysaccharides in vaccines is not associated with risk of autism. The Journal of Pediatrics, 163, 561–567.

Dougherty, D.M., Marsh, D.M., Mathias, C.W., & Swann, A.C. (2005). The conceptualization of impulsivity: Bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Psychiatric Times, 22(8), 32-35.

Dunn, J., & Munn, P. (1987). Development of justification in disputes with mother and sibling. Developmental Psychology, 23, 791-798.

Dyer, S., & Moneta, G. B. (2006). Frequency of parallel, associative, and cooperative play in British children of different socio-economic status. Social Behavior and Personality, 34(5), 587-592.

Economist Data Team. (2017). Parents now spend twice as much time with their children as 50 years ago. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2017/11/27/parents-now-spend-twice-as-much-time-with-their-children-as-50-years-ago

Epley, N., Morewedge, C. K., & Keysar, B. (2004). Perspective taking in children and adults: Equivalent egocentrism but differential correction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 760–768.

Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. NY: Norton & Company.

Evans, D. W., Gray, F. L., & Leckman, J. F. (1999). The rituals, fears and phobias of young children: Insights from development, psychopathology and neurobiology. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 29(4), 261-276. doi:10.1023/A:1021392931450

Evans, D. W. & Leckman, J. F. (2015) Origins of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Developmental and evolutionary perspectives. In D. Cicchetti and D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology (2nd edition). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons. doi: 10.1002/9780470939406.ch10

Fay-Stammbach, T., Hawes, D. J., & Meredith, P. (2014). Parenting influences on executive function in early childhood: A review. Child Development Perspectives, 8(4), 258-264.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R.F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998).

Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Finkelhorn, D., Hotaling, G., Lewis, I. A., & Smith, C. (1990). Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse and Neglect, 14(1), 19-28.

Frank, G., Plunkett, S. W., & Otten, M. P. (2010). Perceived parenting, self-esteem, and general self-efficacy of Iranian American adolescents. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 19, 738-746.

Galotti, K. M. (2018). Cognitive psychology: In and out of the laboratory (6th Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Garrett, B. (2015). Brain and behavior: An introduction to biological psychology (4th Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gauthier, J., Siddiqui, T. J., Huashan, P., Yokomaku, D., Hamdan, F. F., Champagne, N., . . . Rouleau, G.A. (2011). Truncating mutations in NRXN2 and NRXN1 in autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Human Genetics, 130, 563–573.

Gecas, V., & Seff, M. (1991). Families and adolescents. In A. Booth (Ed.), Contemporary families: Looking forward, looking back. Minneapolis, MN: National Council on Family Relations.

Gentile, D.A., & Walsh, D.A. (2002). A normative study of family media habits. Applied Developmental Psychology, 23, 157-178.

Gernhardt, A., Rubeling, H., & Keller, H. (2015). Cultural perspectives on children’s tadpole drawings: At the interface between representation and production. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 812. doi: 0.3389/fpsyg.2015.00812. 159

Gershoff, E. T. (2008). Report on physical punishment in the United States: What research tell us about its effects on children. Columbus, OH: Center for Effective Discipline.

Glass, E., Sachse, S., & von Suchodoletz, W. (2008). Development of auditory sensory memory from 2 to 6 years: An MMN study. Journal of Neural Transmission, 115(8), 1221-1229.doi:10.1007/s00702-008-0088-6

Gleason, T. R. (2002). Social provisions of real and imaginary relationships in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 38, 979-992.

Gleason, T. R., & Hohmann, L. M. (2006). Concepts of real and imaginary friendships in early childhood. Social Development, 15, 128-144.

Gleason, T. R., Sebanc, A. M., & Hartup, W. W. (2000). Imaginary companions of preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 36(4), 419-428.

Gomes, G. Sussman, E., Ritter, W., Kurtzberg, D., Vaughan, H. D. Jr., & Cowen, N. (1999). Electrophysiological evidence of development changes in the duration of auditory sensory memory. Developmental Psychology, 35, 294-302.

Goodvin, R., Meyer, S. Thompson, R.A., & Hayes, R. (2008). Self-understanding in early childhood: Associations with child attachment security and maternal negative affect. Attachment & Human Development, 10(4), 433-450.

Gopnik, A., & Wellman, H.M. (2012). Reconstructing constructivism: Causal models, Bayesian learning mechanisms, and the theory theory. Psychological Bulletin, 138(6), 1085-1108.

Guy, J., Rogers, M., & Cornish, K. (2013). Age-related changes in visual and auditory sustained attention in preschool-aged children. Child Neuropsychology, 19(6), 601–614. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2012.710321

Hammer C. S., Hoff, E., Uchikosh1, Y., Gillanders, C., Castro, D., & Sandilos, L. E. (2014). The language literacy development of young dual language learners: A critical review. Early Child Research Quarterly, 29(4), 715-733.

Harter, S., & Pike, R. (1984). The pictorial scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children. Child Development, 55, 1969-1982.

Harvard University. (2019). Center on the developing child: Toxic stress. Retrieved from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/

Herrmann, E., Misch, A., Hernandez-Lloreda, V., & Tomasello, M. (2015). Uniquely human self-control begins at school age. Developmental Science, 18(6), 979-993. doi:10.1111/desc.12272.

Herrmann, E., & Tomasello, M. (2015). Focusing and shifting attention in human children (homo sapiens) and chimpanzees (pan troglodytes). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 129(3), 268–274. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0039384

Hoff, E. (2018). Bilingual development in children of immigrant families. Child Development Perspectives, 12(2), 80-86.

Howe, N., Rinaldi, C. M., Jennings, M., & Petrakos, H. (2002). “No! The lambs can stay out because they got cozies”: Constructive and destructive sibling conflict, pretend play, and social understanding. Child Development, 73, 1406-1473.

Hughes, V. (2007). Mercury rising. Nature Medicine, 13, 896-897.

Imai, M., Li, L., Haryu, E., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Shigematsu, J. (2008). Novel noun and verb learning in Chinese, English, and Japanese children: Universality and language-specificity in novel noun and verb learning. Child Development, 79, 979-1000.

Jarne, P., & Auld, J. R. (2006). Animals mix it up too: The distribution of self-fertilization among hermaphroditic animals. Evolution, 60, 1816–1824.

Jones, P.R., Moore, D.R., & Amitay, S. (2015). Development of auditory selective attention: Why children struggle to hear in noisy environments. Developmental Psychology, 51(3), 353–369. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038570

Kalat, J. W. (2016). Biological Psychology (12th Ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage.

Kaushanskaya, M., Gross, M., & Buac, M. (2014). Effects of classroom bilingualism on task-shifting, verbal memory, and word learning in children. Developmental Science, 17(4), 564-583.

Kellogg, R. (1969). Handbook for Rhoda Kellogg: Child art collection. Washington D. C.: NCR/Microcard Editions.

Kemple, K.M., (1995). Shyness and self-esteem in early childhood. Journal of Humanistic Education and Development, 33(4), 173-182.

Kimmel, M. S. (2008). The gendered society (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kinney, D. K., Barch, D. H., Chayka, B., Napoleon, S., & Munir, K. M. (2009). Environmental risk factors for autism: Do they help or cause de novo genetic mutations that contribute to the disorder? Medical Hypotheses, 74, 102–106.