7 Emerging and Early Adulthood

Historically, early adulthood spanned from approximately 18 (the end of adolescence) until 40 to 45 (beginning of middle adulthood). More recently, developmentalists have divided this age period into two separate stages: Emerging adulthood followed by early adulthood. Although these age periods differ in their physical, cognitive, and social development, overall the age period from 18 to 45 is a time of peak physical capabilities and the emergence of more mature cognitive development, financial independence, and intimate relationships.

7.1 Emerging Adulthood

Explain emerging adulthood

Explain how emerging adulthood differs from adolescence and adulthood

Describe economic and cultural variations of emerging adulthood

Identify the markers of adulthood

Identify where emerging and early adults currently live

7.1.1 Emerging Adulthood Defined

Emerging adulthood is the period between the late teens and early twenties; ages 18-25, although some researchers have included up to age 29 in the definition (Society for the Study of Emerging Adulthood, 2016). Jeffrey Arnett (2000) argues that emerging adulthood is neither adolescence nor is it young adulthood. Individuals in this age period have left behind the relative dependency of childhood and adolescence but have not yet taken on the responsibilities of adulthood. “Emerging adulthood is a time of life when many different directions remain possible, when little about the future is decided for certain, when the scope of independent exploration of life’s possibilities is greater for most people than it will be at any other period of the life course” (Arnett, 2000, p. 469). Arnett identified five characteristics of emerging adulthood that distinguished it from adolescence and young adulthood (Arnett, 2006).

It is the age of identity exploration. In 1950, Erik Erikson proposed that it was during adolescence that humans wrestled with the question of identity. Yet, even Erikson (1968) commented on a trend during the 20th century of a “prolonged adolescence” in industrialized societies. Today, most identity development occurs during the late teens and early twenties rather than adolescence. It is during emerging adulthood that people are exploring their career choices and ideas about intimate relationships, setting the foundation for adulthood.

Arnett also described this time period as the age of instability (Arnett, 2000; Arnett, 2006). Exploration generates uncertainty and instability. Emerging adults change jobs, relationships, and residences more frequently than other age groups.

This is also the age of self-focus. Being self-focused is not the same as being “self-centered.” Adolescents are more self-centered than emerging adults. Arnett reports that in his research, he found emerging adults to be very considerate of the feelings of others, especially their parents. They now begin to see their parents as people not just parents, something most adolescents fail to do (Arnett, 2006). Nonetheless, emerging adults focus more on themselves, as they realize that they have few obligations to others and that this is the time where they can do what they want with their life.

This is also the age of feeling in-between. When asked if they feel like adults, more 18 to 25 year-olds answer “yes and no” than do teens or adults over the age of 25 (Arnett, 2001). Most emerging adults have gone through the changes of puberty, are typically no longer in high school, and many have also moved out of their parents’ home. Thus, they no longer feel as dependent as they did as teenagers. Yet, they may still be financially dependent on their parents to some degree, and they have not completely attained some of the indicators of adulthood, such as finishing their education, obtaining a good full-time job, being in a committed relationship, or being responsible for others. It is not surprising that Arnett found that 60% of 18 to 25 year-olds felt that in some ways they were adults, but in some ways, they were not (Arnett, 2001).

Emerging adulthood is the age of possibilities. It is a time period of optimism as more 18 to 25 year-olds feel that they will someday get to where they want to be in life. Arnett (2000, 2006) suggests that this optimism is because these dreams have yet to be tested. For example, it is easier to believe that you will eventually find your soul mate when you have yet to have had a serious relationship. It may also be a chance to change directions, for those whose lives up to this point have been difficult. The experiences of children and teens are influenced by the choices and decisions of their parents. If the parents are dysfunctional, there is little a child can do about it. In emerging adulthood, people can move out and move on. They have the chance to transform their lives and move away from unhealthy environments. Even those whose lives were happier and more fulfilling as children, now have the opportunity in emerging adulthood to become independent and make decisions about the direction they would like their life to take.

Socioeconomic Class and Emerging Adulthood: The theory of emerging adulthood was initially criticized as only reflecting upper middle-class, college-attending young adults in the United States and not those who were working class or poor (Arnett, 2016). Consequently, Arnett reviewed results from the 2012 Clark University Poll of Emerging Adults, whose participants were demographically similar to the United States population. Results primarily indicated consistencies across aspects of the theory, including positive and negative perceptions of the time-period and views on education, work, love, sex, and marriage. Two significant differences were found, the first being that emerging adults from lower socioeconomic classes identified more negativity in their emotional lives, including higher levels of depression. Secondly, those in the lowest socioeconomic group were more likely to agree that they had not been able to find sufficient financial support to obtain the education they believed they needed. Overall, Arnett concluded that emerging adulthood exists wherever there is a period between the end of adolescence and entry into adult roles, but acknowledging social, cultural, and historical contexts was also important.

7.1.2 Cultural Variations

The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood originally were based on research involving about Americans between ages 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2004, 2016). To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally?

The answer to this question depends greatly on what part of the world is considered. Demographers make a useful distinction between the developing countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population and the economically developed countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), including the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The current population of OECD countries (also called developed countries) is 1.2 billion, about 18% of the total world population (United Nations Development Programme, 2011). The rest of the human population resides in developing countries, which have much lower median incomes, much lower median educational attainment, and much higher incidence of illness, disease, and early death. Let us consider emerging adulthood in other OECD countries as little is known about the experiences of 18-25 year-olds in developing countries.

The same demographic changes as described above for the United States have taken place in other OECD countries as well. This is true of participation in postsecondary education, as well as median ages for entering marriage and parenthood (UNdata, 2010). However, there is also substantial variability in how emerging adulthood is experienced across OECD countries. Europe is the region where emerging adulthood is longest and most leisurely. The median ages for entering marriage and parenthood are near 30 in most European countries (Douglass, 2007). Europe today is the location of the most affluent, generous, and egalitarian societies in the world, in fact, in human history (Arnett, 2007). Governments pay for tertiary education, assist young people in finding jobs, and provide generous unemployment benefits for those who cannot find work. In northern Europe, many governments also provide housing support. Emerging adults in European societies make the most of these advantages, gradually making their way to adulthood during their twenties while enjoying travel and leisure with friends.

The lives of Asian emerging adults in developed countries, such as Japan and South Korea, are in some ways similar to the lives of emerging adults in Europe and in some ways strikingly different. Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults tend to enter marriage and parenthood around age 30 (Arnett, 2011). Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults in Japan and South Korea enjoy the benefits of living in affluent societies with generous social welfare systems that provide support for them in making the transition to adulthood, including free university education and substantial unemployment benefits.

However, in other ways, the experience of emerging adulthood in Asian OECD countries is markedly different than in Europe. Europe has a long history of individualism, and today’s emerging adults carry that legacy with them in their focus on self-development and leisure during emerging adulthood. In contrast, Asian cultures have a shared cultural history emphasizing collectivism and family obligations.

Although Asian cultures have become more individualistic in recent decades, as a consequence of globalization, the legacy of collectivism persists in the lives of emerging adults. They pursue identity explorations and self-development during emerging adulthood, like their American and European counterparts, but within narrower boundaries set by their sense of obligations to others, especially their parents (Phinney & Baldelomar, 2011). For example, in their views of the most important criteria for becoming an adult, emerging adults in the United States and Europe consistently rank financial independence among the most important markers of adulthood. In contrast, emerging adults with an Asian cultural background especially emphasize becoming capable of supporting parents financially as among the most important criteria (Arnett, 2003; Nelson, Badger, & Wu, 2004). This sense of family obligation may curtail their identity explorations in emerging adulthood to some extent, as they pay more heed to their parents’ wishes about what they should study, what job they should take, and where they should live than emerging adults do in the West (Rosenberger, 2007).

Is your culture one that promotes romantic relationships for emerging adults? Or does it encourage you to wait till you’re older? What would it be like to live in the opposite culture?

7.1.3 When Does Adulthood Begin?

According to Rankin and Kenyon (2008), historically the process of becoming an adult was more clearly marked by rites of passage. For many, marriage and parenthood were considered entry into adulthood. However, these role transitions are no longer considered the important markers of adulthood (Arnett, 2001). Economic and social changes have resulted in more young adults attending college (Rankin & Kenyon, 2008) and a delay in marriage and having children (Arnett & Taber, 1994; Laursen & Jensen-Campbell, 1999) Consequently, current research has found financial independence and accepting responsibility for oneself to be the most important markers of adulthood in Western culture across age (Arnett, 2001) and ethnic groups (Arnett, 2004).

In looking at college students’ perceptions of adulthood, Rankin and Kenyon (2008) found that some students still view rites of passage as important markers. College students who had placed more importance on role transition markers, such as parenthood and marriage, belonged to a fraternity/sorority, were traditionally aged (18–25), belonged to an ethnic minority, were of a traditional marital status; i.e., not cohabitating, or belonged to a religious organization, particularly for men. These findings supported the view that people holding collectivist or more traditional values place more importance on role transitions as markers of adulthood. In contrast, older college students and those cohabitating did not value role transitions as markers of adulthood as strongly.

7.1.4 Young Adults Living Arrangements

In 2014, for the first time in more than 130 years, adults 18 to 34 were more likely to be living in their parents’ home than they were to be living with a spouse or partner in their own household (Fry, 2016). The current trend is that young Americans are not choosing to settle down romantically before age 35. Since 1880, living with a romantic partner was the most common living arrangement among young adults. In 1960, 62% of America’s 18- to 34-year-olds were living with a spouse or partner in their own household, while only 20% were living with their parents.

By 2014, 31.6% of early adults were living with a spouse or partner in their own household, while 32.1% were living in the home of their parent(s). Another 14% of early adults lived alone, were a single parent, or lived with one or more roommates. The remaining 22% lived in the home of another family member (such as a grandparent, in-law, or sibling), a non-relative, or in group quarters (e.g., college dormitories). Comparing ethnic groups, 36% of black and Hispanic early adults lived at home, while 30% of white young adults lived at home.

As can be seen in Figure 7.5, gender differences in living arrangements are also noted in that young men were living with parents at a higher rate than young women. In 2014, 35% of young me were residing with their parents, while 28% were living with a spouse or partner in their own household. Young women were more likely to be living with a spouse or partner (35%) than living with their parents (29%). Additionally, more young women (16%) than young men (13%) were heading up a household without a spouse or partner, primarily because women are more likely to be single parents living with their children. Lastly, young men (25%) were more likely than young women (19%) to be living in the home of another family member, a non-relative, or in some type of group quarters (Fry, 2016).

What are some factors that help explain these changes in living arrangements? First, early adults are postponing marriage or choosing not to marry or cohabitate. Lack of employment and lower wages have especially contributed to males residing with their parents. Men who are employed are less likely to live at home. Wages for young men (adjusting for inflation) have been falling since 1970 and correlate with the rise in young men living with their parents. The recent recession and recovery (2007-present) has also contributed to the increase in early adults living at home. College enrollments increased during the recession, which further increased early adults living at home. However, once early adults possess a college degree, they are more likely to establish their own households (Fry, 2016).

7.2 Physical Development in Emerging and Early Adulthood

Summarize the overall physical growth in early adulthood

Describe statistics, possible causes, and consequences of obesity

Explain how early adulthood is a healthy, yet risky time of life

Identify the risk factors for substance use

Describe the changes in brain maturation

Describe gender in adulthood, including gender minorities and stress

Define sexuality and explain the female and male reproductive systems

Describe the brain areas and hormones responsible for sexual behavior

Identify sexually transmitted infections

Describe cultural views related to sexuality

Describe research on sexual orientation

7.2.1 The Physiological Peak

People in their mid-twenties to mid-forties are considered to be in early adulthood. By the time we reach early adulthood, our physical maturation is complete, although our height and weight may increase slightly. Those in their early twenties are probably at the peak of their physiological development, including muscle strength, reaction time, sensory abilities, and cardiac functioning. The reproductive system, motor skills, strength, and lung capacity are all operating at their best. Most professional athletes are at the top of their game during this stage, and many women have children in the early-adulthood years (Boundless, 2016).

The aging process actually begins during early adulthood. Around the age of 30, many changes begin to occur in different parts of the body. For example, the lens of the eye starts to stiffen and thicken, resulting in changes in vision (usually affecting the ability to focus on close objects). Sensitivity to sound decreases; this happens twice as quickly for men as for women. Hair can start to thin and become gray around the age of 35, although this may happen earlier for some individuals and later for others. The skin becomes drier and wrinkles start to appear by the end of early adulthood. This includes a decline in response time and the ability to recover quickly from physical exertion. The immune system also becomes less adept at fighting off illness, and reproductive capacity starts to decline (Boundless, 2016).

7.2.2 Obesity

Although at the peak of physical health, a concern for early adults is the current rate of obesity. Results from the National Center for Health Statistics indicated that an estimated 70.7% of U.S. adults aged 20 and over were overweight in 2012 (CDC, 2015b) and by 2016, 39.8% were considered obese (Hales, Carroll, Fryar, & Ogden, 2017)). Body mass index (BMI), expressed as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2), is commonly used to classify overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9), obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 30.0), and extreme obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 40.0). The current statistics are an increase from the 2013-2014 statistics that indicated that an estimated 35.1% were obese, and 6.4% extremely obese (Fryar, Carroll, & Ogden, 2014). The CDC also indicated that one’s 20s are the prime time to gain weight as the average person gains one to two pounds per year from early adulthood into middle adulthood. The average man in his 20s weighs around 185 pounds and by his 30s weighs approximately 200 pounds. The average American woman weighs 162 pounds in her 20s and 170 pounds in her 30s.

The American obesity crisis is also reflected worldwide (Wighton, 2016). In 2014, global obesity rates for men were measured at 10.8% and among women 14.9%. This translates to 266 million obese men and 375 million obese women in the world, and more people were identified as obese than underweight. Although obesity is seen throughout the world, more obese men and women live in China and the USA than in any other country. Figure 7.6 illustrates how waist circumference is also used as a measure of obesity. Figure 7.7 demonstrates the percentage growth for youth (2-19 years) and adults (20-60+ years) identified as obese between 1999 and 2016.

Causes of Obesity: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2016), obesity originates from a complex set of contributing factors, including one’s environment, behavior, and genetics. Societal factors include culture, education, food marketing and promotion, the quality of food, and the physical activity environment available. Behaviors leading to obesity include diet, the amount of physical activity, and medication use. Lastly, there does not appear to be a single gene responsible for obesity. Rather, research has identified variants in several genes that may contribute to obesity by increasing hunger and food intake. Another genetic explanation is the mismatch between today’s environment and “energy-thrifty genes” that multiplied in the distant past, when food sources were unpredictable. The genes that helped our ancestors survive occasional famines are now being challenged by environments in which food is plentiful all the time. Overall, obesity most likely results from complex interactions among the environment and multiple genes.

Obesity Health Consequences: Obesity is considered to be one of the leading causes of death in the United States and worldwide. Additionally, the medical care costs of obesity in the United States were estimated to be $147 billion in 2008. According to the CDC (2016) compared to those with a normal or healthy weight, people who are obese are at increased risk for many serious diseases and health conditions including:

All-causes of death (mortality)

High blood pressure (Hypertension)

High LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, or high levels of triglycerides (Dyslipidemia)

Type 2 diabetes

Coronary heart disease

Stroke

Gallbladder disease

Osteoarthritis (a breakdown of cartilage and bone within a joint)

Sleep apnea and breathing problems

Some cancers (endometrial, breast, colon, kidney, gallbladder, and liver)

Low quality of life

Mental illness, such as clinical depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders

Body pain and difficulty with physical functioning

7.2.3 A Healthy, But Risky Time

Doctor’s visits are less frequent in early adulthood than for those in midlife and late adulthood and are necessitated primarily by injury and pregnancy (Berger, 2005). However, the top five causes of death in emerging and early adulthood are non-intentional injury (including motor vehicle accidents), homicide, and suicide with cancer and heart disease completing the list (Heron, & Smith, 2007). Rates of violent death (homicide, suicide, and accidents) are highest among young adult males, and vary by race and ethnicity. Rates of violent death are higher in the United States than in Canada, Mexico, Japan, and other selected countries. Males are 3 times more likely to die in auto accidents than are females (Frieden, 2011).

Alcohol Abuse: A significant contributing factor to risky behavior is alcohol. According to the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), 2016) 88% of people ages 18 or older reported that they drank alcohol at some point in their lifetime; 71% reported that they drank in the past year; and 57% reported drinking in the past month. Additionally, 6.7% reported that they engaged in heavy drinking in the past month. Heavy drinking is defined as drinking five or more drinks on the same occasion on each of five or more days in the past 30 days. Nearly 88,000 people (approximately 62,000 men and 26,000 women) die from alcohol-related causes annually, making it the fourth leading preventable cause of death in the United States. In 2014, alcohol-impaired driving fatalities accounted for 9,967 deaths (31% of overall driving fatalities).

The NIAAA defines binge drinking when blood alcohol concentration levels reach 0.08 g/dL. This typically occurs after four drinks for women and five drinks for men in approximately two hours. In 2014, 25% of people ages 18 or older reported that they engaged in binge drinking in the past month. According to the NIAAA (2015) “Binge drinking poses serious health and safety risks, including car crashes, drunk-driving arrests, sexual assaults, and injuries. Over the long term, frequent binge drinking can damage the liver and other organs,” (p. 1).

Alcohol and College Students: Results from the 2014 survey demonstrated a difference between the amount of alcohol consumed by college students and those of the same age who are not in college (NIAAA, 2016). Specifically, 60% of full-time college students’ ages 18–22 drank alcohol in the past month compared with 51.5% of other persons of the same age not in college. In addition, 38% of college students’ ages 18–22 engaged in binge drinking; that is, five or more drinks on one occasion in the past month, compared with 33.5% of other persons of the same age. Lastly, 12% of college students’ (ages 18–22) engaged in heavy drinking; that is, binge drinking on five or more occasions per month, in the past month. This compares with 9.5% of other emerging adults not in college.

The consequences for college drinking are staggering, and the NIAAA (2016) estimates that each year the following occur:

1,825 college students between the ages of 18 and 24 die from alcohol-related unintentional injuries, including motor-vehicle crashes.

696,000 students between the ages of 18 and 24 are assaulted by another student who has been drinking.

Roughly 1 in 5 college students meet the criteria for an Alcohol Use Disorder.

About 1 in 4 college students report academic consequences from drinking, including missing class, falling behind in class, doing poorly on exams or papers, and receiving lower grades overall. (p. 1)

97,000 students between the ages of 18 and 24 report experiencing alcohol-related sexual assault or date rape.

The role alcohol plays in predicting acquaintance rape on college campuses is of particular concern. “Alcohol use in one the strongest predictors of rape and sexual assault on college campuses,” (Carroll, 2016, p. 454). Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher and Martin (2009) found that over 80% of sexual assaults on college campuses involved alcohol. Being intoxicated increases a female’s risk of being the victim of date or acquaintance rape (Carroll, 2007). Females are more likely to blame themselves and to be blamed by others if they were intoxicated when raped. College students view perpetrators who were drinking as less responsible, and victims who were drinking as more responsible for the assaults (Untied, Orchowski, Mastroleo, & Gidycz, 2012).

Factors Affecting College Students’ Drinking: Several factors associated with college life affect a student’s involvement with alcohol (NIAAA, 2015). These include the pervasive availability of alcohol, inconsistent enforcement of underage drinking laws, unstructured time, coping with stressors, and limited interactions with parents and other adults. Due to social pressures to conform and expectations when entering college, the first six weeks of freshman year are an especially susceptible time for students. Additionally, more drinking occurs in colleges with active Greek systems and athletic programs. Alcohol consumption is lowest among students living with their families and commuting, while it is highest among those living in fraternities and sororities.

College Strategies to Curb Drinking: Strategies to address college drinking involve the individual-level and campus community as a whole. Identifying at-risk groups, such as first year students, members of fraternities and sororities, and athletes has proven helpful in changing students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior regarding alcohol (NIAAA, 2015). Interventions include education and awareness programs, as well as intervention by health professionals. At the college-level, reducing the availability of alcohol has proven effective by decreasing both consumption and negative consequences.

Non-Alcohol Substance Use: Illicit drug use peaks between the ages of 19 and 22 and then begins to decline. Additionally, 25% of those who smoke cigarettes, 33% of those who smoke marijuana, and 70% of those who abuse cocaine began using after age 17 (Volkow, 2004). Emerging adults (18 to 25) are the largest abusers of prescription opioid pain relievers, anti-anxiety medications, and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder medication (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2015). In 2016, opioid misuse within the past 12 months was reported by 3.6% of 12-17 year-olds and was twice as high among those 18-25 (Office of Adolescent Health, 2019). In 2014 more than 1700 emerging adults died from a prescription drug overdose. This is an increase of four times since 1999. Additionally, for every death there were 119 emergency room visits.

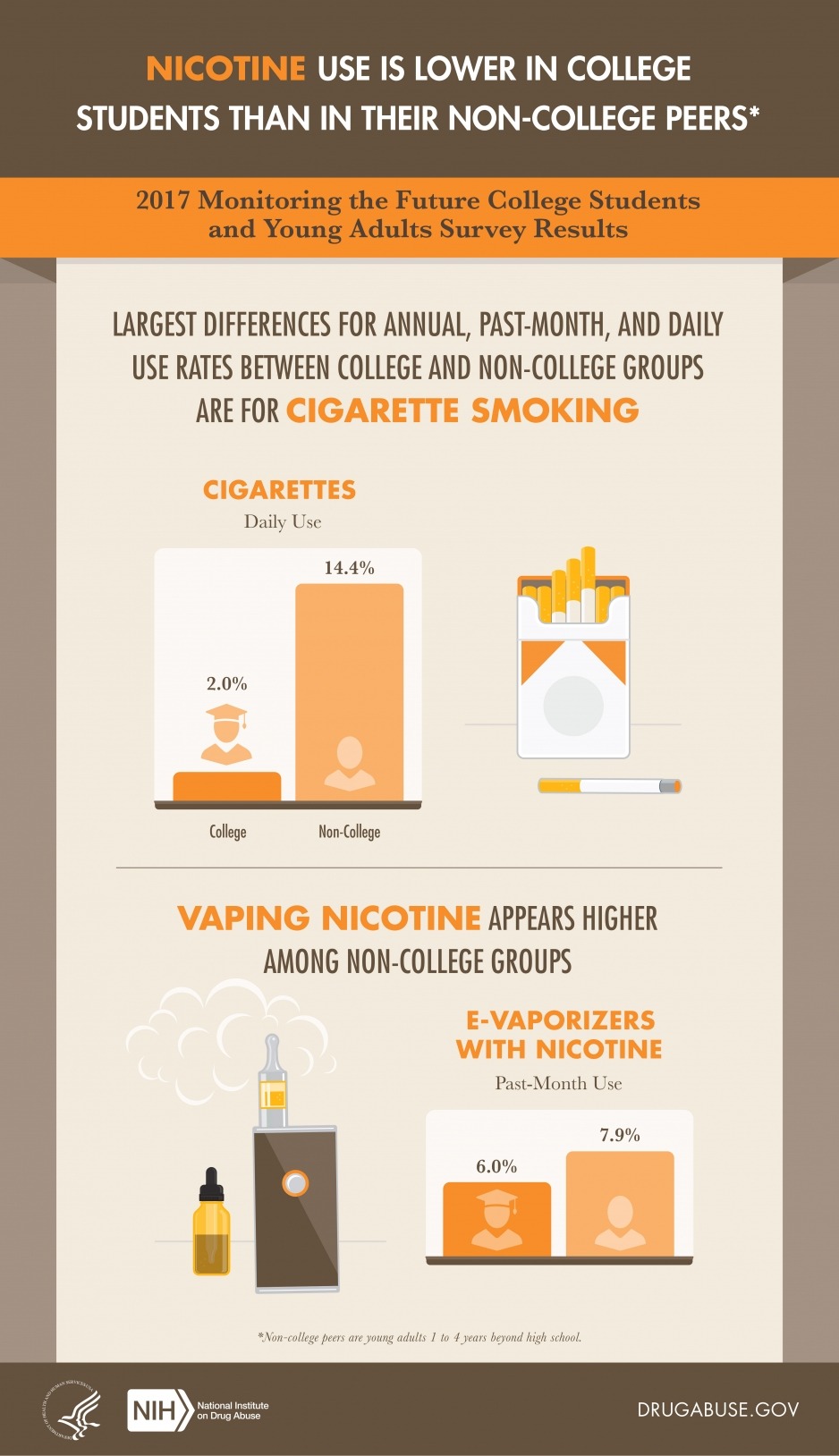

Daily marijuana use is at the highest level in three decades (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2015). For those in college, 2014 data indicate that 6% of college students smoke marijuana daily, while only 2% smoked daily in 1994. For noncollege students of the same age, the daily percentage is twice as high (approximately 12%). Additionally, according to a recent survey by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (2018), daily cigarette smoking is lower for those in college in comparison to non-college groups (see Figure 7.10).

Rates of violent death are influenced by substance use which peaks during emerging and early adulthood. Drugs impair judgment, reduce inhibitions, and alter mood, all of which can lead to dangerous behavior. Reckless driving, violent altercations, and forced sexual encounters are some examples. Drug and alcohol use increase the risk of sexually transmitted infections because people are more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior when under the influence. This includes having sex with someone who has had multiple partners, having anal sex without the use of a condom, having multiple partners, or having sex with someone whose history is unknown. Lastly, as previously discussed, drugs and alcohol ingested during pregnancy have a teratogenic effect on the developing embryo and fetus.

7.2.4 Gender

As previously discussed in chapter 4, gender is the cultural, social and psychological meanings associated with masculinity and feminity. A person’s sense of self as a member of a particular gender is known as gender identity. Because gender is considered a social construct, meaning that it does not exist naturally, but is instead a concept that is created by cultural and societal norms, there are cultural variations on how people express their gender identity. For example, in American culture, it is considered feminine to wear a dress or skirt. However, in many Middle Eastern, Asian, and African cultures, dresses or skirts (often referred to as sarongs, robes, or gowns) can be considered masculine. Similarly, the kilt worn by a Scottish male does not make him appear feminine in his culture.

For many adults, the drive to adhere to masculine and feminine gender roles, or the societal expectations associated with being male or female, continues throughout life. In American culture, masculine roles have traditionally been associated with strength, aggression, and dominance, while feminine roles have traditionally been associated with passivity, nurturing, and subordination. Men tend to outnumber women in professions such as law enforcement, the military, and politics, while women tend to outnumber men in care-related occupations such as childcare, healthcare, and social work. These occupational roles are examples of stereotypical American male and female behavior, derived not from biology or genetics, but from our culture’s traditions. Adherence to these roles may demonstrate fulfillment of social expectations, however, not necessarily personal preferences (Diamond, 2002).

Consequently, many adults are challenging gender labels and roles, and the long-standing gender binary; that is, categorinzing humans as only female and male, has been undermined by current psychological research (Hyde, Bigler, Joel, Tate, & van Anders, 2019). The term gender now encompasses a wide range of possible identities, including cisgender, transgender, agender, genderfluid, genderqueer, gender nonconforming, bigender, pangender, ambigender, non-gendered, intergender, and Two-spirit which is a modern umbrella term used by some indigenous North Americans to describe gender-variant individuals in their communities (Carroll, 2016). Hyde et al. (2019) advocates for a conception of gender that stresses multiplicity and diversity and uses multiple categories that are not mutually exclusive.

Gender Minority Discrimination: Gender nonconforming people are much more likely to experience harassment, bullying, and violence based on their gender identity; they also experience much higher rates of discrimination in housing, employment, healthcare, and education (Borgogna, McDermott, Aita, & Kridel, 2019; National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). Transgender individuals of color face additional financial, social, and interpersonal challenges, in comparison to the transgender community as a whole, as a result of structural racism. Black transgender people reported the highest level of discrimination among all transgender individuals of color. As members of several intersecting minority groups, transgender people of color, and transgender women of color in particular, are especially vulnerable to employment discrimination, poor health outcomes, harassment, and violence. Consequently, they face even greater obstacles than white transgender individuals and cisgender members of their own race.

Gender Minority Status and Mental Health: Using data from over 43,000 college students, Borgona et al. (2019) examined mental health differences among several gender groups, including those identifying as cisgender, transgender and gender nonconforming. Results indicated that participants who identified as transgender and gender nonconforming had significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression than those identifying as cisgender. Bargona et al. explained the higher rates of anxiety and depression using the minority stress model, which states that an unaccepting social environment results in both external and internal stress which contributes to poorer mental health. External stressors include discrimination, harassment, and prejudice, while internal stressors include negative thoughts, feelings and emotions resulting from one’s identity. Borgona et al. recommends that mental health services that are sensitive to both gender minority and sexual minority statatus be available.

The transgender children discussed in chapter 4 may, when they become an adult, alter their bodies through medical interventions, such as surgery and hormonal therapy, so that their physical being is better aligned with gender identity. However, not all transgender individuals choose to alter their bodies or physically transition. Many will maintain their original anatomy but may present themselves to society as a different gender, often by adopting the dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, or other characteristics typically assigned to a certain gender. It is important to note that people who cross-dress, or wear clothing that is traditionally assigned to the opposite gender, such as transvestites, drag kings, and drag queens, do not necessarily identify as transgender (though some do). People often confuse the term transvestite, which is the practice of dressing and acting in a style or manner traditionally associated with another sex (APA, 2013) with transgender. Cross-dressing is typically a form of self-expression, entertainment, or personal style, and not necessarily an expression about one’s gender identity.

7.2.5 Sexuality

Human sexuality refers to people’s sexual interest in and attraction to others, as well as their capacity to have erotic experiences and responses. Sexuality may be experienced and expressed in a variety of ways, including thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviors, practices, roles, and relationships. These may manifest themselves in biological, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual aspects. The biological and physical aspects of sexuality largely concern the human reproductive functions, including the human sexual-response cycle and the basic biological drive that exists in all species. Emotional aspects of sexuality include bonds between individuals that are expressed through profound feelings or physical manifestations of love, trust, and care. Social aspects deal with the effects of human society on one’s sexuality, while spirituality concerns an individual’s spiritual connection with others through sexuality. Sexuality also impacts, and is impacted by cultural, political, legal, philosophical, moral, ethical, and religious aspects of life.

The Sexual Response Cycle: Sexual motivation, often referred to as libido, is a person’s overall sexual drive or desire for sexual activity. This motivation is determined by biological, psychological, and social factors. In most mammalian species, sex hormones control the ability to engage in sexual behaviors. However, sex hormones do not directly regulate the ability to copulate in primates (including humans); rather, they are only one influence on the motivation to engage in sexual behaviors. Social factors, such as work and family, also have an impact, as do internal psychological factors like personality and stress. Sex drive may also be affected by hormones, medical conditions, medications, lifestyle stress, pregnancy, and relationship issues.

The sexual response cycle is a model that describes the physiological responses that take place during sexual activity. According to Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin (1948), the cycle consists of four phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution. The excitement phase is the phase in which the intrinsic (inner) motivation to pursue sex arises. The plateau phase is the period of sexual excitement with increased heart rate and circulation that sets the stage for orgasm. Orgasm is the release of tension, and the resolution period is the unaroused state before the cycle begins again.

The Brain and Sex: The brain is the structure that translates the nerve impulses from the skin into pleasurable sensations. It controls nerves and muscles used during sexual behavior. The brain regulates the release of hormones, which are believed to be the physiological origin of sexual desire. The cerebral cortex, which is the outer layer of the brain that allows for thinking and reasoning, is believed to be the origin of sexual thoughts and fantasies. Beneath the cortex is the limbic system, which consists of the amygdala, hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, and septal area. These structures are where emotions and feelings are believed to originate, and they are important for sexual behavior.

The hypothalamus is the most important part of the brain for sexual functioning. This is the small area at the base of the brain consisting of several groups of nerve-cell bodies that receives input from the limbic system. Studies with lab animals have shown that destruction of certain areas of the hypothalamus causes complete elimination of sexual behavior. One of the reasons for the importance of the hypothalamus is that it controls the pituitary gland, which secretes hormones that control the other glands of the body.

Hormones: Several important sexual hormones are secreted by the pituitary gland. Oxytocin, also known as the hormone of love, is released during sexual intercourse when an orgasm is achieved. Oxytocin is also released in females when they give birth or are breast feeding; it is believed that oxytocin is involved with maintaining close relationships. Both prolactin and oxytocin stimulate milk production in females. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is responsible for ovulation in females by triggering egg maturity; it also stimulates sperm production in males. Luteinizing hormone (LH) triggers the release of a mature egg in females during the process of ovulation.

In males, testosterone appears to be a major contributing factor to sexual motivation. Vasopressin is involved in the male arousal phase, and the increase of vasopressin during erectile response may be directly associated with increased motivation to engage in sexual behavior.

The relationship between hormones and female sexual motivation is not as well understood, largely due to the overemphasis on male sexuality in Western research. Estrogen and progesterone typically regulate motivation to engage in sexual behavior for females, with estrogen increasing motivation and progesterone decreasing it. The levels of these hormones rise and fall throughout a woman’s menstrual cycle. Research suggests that testosterone, oxytocin, and vasopressin are also implicated in female sexual motivation in similar ways as they are in males, but more research is needed to understand these relationships.

Sexual Responsiveness Peak: Men and women tend to reach their peak of sexual responsiveness at different ages. For men, sexual responsiveness tends to peak in the late teens and early twenties. Sexual arousal can easily occur in response to physical stimulation or fantasizing. Sexual responsiveness begins a slow decline in the late twenties and into the thirties, although a man may continue to be sexually active. Through time, a man may require more intense stimulation in order to become aroused. Women often find that they become more sexually responsive throughout their 20s and 30s and may peak in the late 30s or early 40s. This is likely due to greater self-confidence and reduced inhibitions about sexuality.

Sexually Transmitted Infections: Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or venereal diseases (VDs), are illnesses that have a significant probability of transmission by means of sexual behavior, including vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral sex. Some STIs can also be contracted by sharing intravenous drug needles with an infected person, as well as through childbirth or breastfeeding.

Common STIs include:

chlamydia;

herpes (HSV-1 and HSV-2);

human papillomavirus (HPV);

gonorrhea;

syphilis;

trichomoniasis;

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2014), there was an increase in the three most common types of STDs in 2014. These include 1.4 million cases of chlamydia, 350,000 cases of gonorrhea, and 20,000 cases of syphilis. Those most affected by STDS include those younger, gay/bisexual males, and females. The most effective way to prevent transmission of STIs is to practice safe sex and avoid direct contact of skin or fluids which can lead to transfer with an infected partner. Proper use of safe-sex supplies (such as male condoms, female condoms, gloves, or dental dams) reduces contact and risk and can be effective in limiting exposure; however, some disease transmission may occur even with these barriers.

Societal Views on Sexuality: Society’s views on sexuality are influenced by everything from religion to philosophy, and they have changed throughout history and are continuously evolving. Historically, religion has been the greatest influence on sexual behavior in the United States; however, in more recent years, peers and the media have emerged as two of the strongest influences, particularly among American teens (Potard, Courtois, & Rusch, 2008). Mass media in the form of television, magazines, movies, and music continues to shape what is deemed appropriate or normal sexuality, targeting everything from body image to products meant to enhance sex appeal. Media serves to perpetuate a number of social scripts about sexual relationships and the sexual roles of men and women, many of which have been shown to have both empowering and problematic effects on people’s (especially women’s) developing sexual identities and sexual attitudes.

Cultural Differences: In the West, premarital sex is normative by the late teens, more than a decade before most people enter marriage. In the United States and Canada, and in northern and eastern Europe, cohabitation is also normative; most people have at least one cohabiting partnership before marriage. In southern Europe, cohabiting is still taboo, but premarital sex is tolerated in emerging adulthood. In contrast, both premarital sex and cohabitation remain rare and forbidden throughout Asia. Even dating is discouraged until the late twenties, when it would be a prelude to a serious relationship leading to marriage. In cross-cultural comparisons, about three fourths of emerging adults in the United States and Europe report having had premarital sexual relations by age 20, versus less than one fifth in Japan and South Korea (Hatfield & Rapson, 2006).

Sexual Orientation: A person’s sexual orientation is their emotional and sexual attraction to a particular gender. It is a personal quality that inclines people to feel romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of a given sex or gender. According to the American Psychological Association (APA) (2016), sexual orientation also refers to a person’s sense of identity based on those attractions, related behaviors, and membership in a community of others who share those attractions. Sexual orientation is independent of gender; for example, a transgender person may identify as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, pansexual, polysexual, asexual, or any other kind of sexuality, just like a cisgender person.

Sexual Orientation on a Continuum: Sexuality researcher Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. To classify this continuum of heterosexuality and homosexuality, Kinsey et al. (1948) created a seven-point rating scale that ranged from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual. Research done over several decades has supported this idea that sexual orientation ranges along a continuum, from exclusive attraction to the opposite sex/gender to exclusive attraction to the same sex/gender (Carroll, 2016).

However, sexual orientation now can be defined in many ways. Heterosexuality, which is often referred to as being straight, is attraction to individuals of the opposite sex/gender, while homosexuality, being gay or lesbian, is attraction to individuals of one’s own sex/gender. Bisexuality was a term traditionally used to refer to attraction to individuals of either male or female sex, but it has recently been used in nonbinary models of sex and gender (i.e., models that do not assume there are only two sexes or two genders) to refer to attraction to any sex or gender. Alternative terms such as pansexuality and polysexuality have also been developed, referring to attraction to all sexes/genders and attraction to multiple sexes/genders, respectively (Carroll, 2016).

Asexuality refers to having no sexual attraction to any sex/gender. According to Bogaert (2015) about one percent of the population is asexual. Being asexual is not due to any physical problems, and the lack of interest in sex does not cause the individual any distress. Asexuality is being researched as a distinct sexual orientation.

Development of Sexual Orientation: According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence. However, this is not always the case, and some do not become aware of their sexual orientation until much later in life. It is not necessary to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation. Some researchers argue that sexual orientation is not static and inborn but is instead fluid and changeable throughout the lifespan.

There is no scientific consensus regarding the exact reasons why an individual holds a particular sexual orientation. Research has examined possible biological, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, but there has been no evidence that links sexual orientation to only one factor (APA, 2016). However, biological explanations, that include genetics, birth order, and hormones will be explored further as many scientists support biological processes occurring during the embryonic and and early postnatal life as playing the main role in sexual orientation (Balthazart, 2018).

Genetics: Using both twin and familial studies, heredity provides one biological explanation for same-sex orientation. Bailey and Pillard (1991) studied pairs of male twins and found that the concordance rate for identical twins was 52%, while the rate for fraternal twins was only 22%. Bailey, Pillard, Neale, and Agyei (1993) studied female twins and found a similar difference with a concordance rate of 48% for identical twins and 16% for fraternal twins. Schwartz, Kim, Kolundzija, Rieger, & Sanders (2010) found that gay men had more gay male relatives than straight men, and sisters of gay men were more likely to be lesbians than sisters of straight men.

Fraternal Birth Order: The fraternal birth order effect indicates that the probability of a boy identifying as gay increases for each older brother born to the same mother (Balthazart, 2018; Blanchard, 2001). According to Bogaret et al. “the increased incidence of homosexuality in males with older brothers results from a progressive immunization of the mother against a male specific cell-adhesion protein that plays a key role in cell-cell interactions, specifically in the process of synapse formation,” (as cited in Balthazart, 2018, p. 234). A meta-analysis indicated that the fraternal birth order effect explains the sexual orientation of between 15% and 29% of gay men.

Hormones: Excess or deficient exposure to hormones during prenatal development has also been theorized as an explanation for sexual orientation. One-third of females exposed to abnormal amounts of prenatal androgens, a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), identify as bisexual or lesbian (Cohen-Bendahan, van de Beek, & Berenbaum, 2005). In contrast, too little exposure to prenatal androgens may affect male sexual orientation by not masculinizing the male brain (Carlson, 2011).

Sexual Orientation Discrimination: The United States is heteronormative, meaning that society supports heterosexuality as the norm. Consider, for example, that homosexuals are often asked, “When did you know you were gay?” but heterosexuals are rarely asked, “When did you know you were straight?” (Ryle, 2011). Living in a culture that privileges heterosexuality has a significant impact on the ways in which non-heterosexual people are able to develop and express their sexuality.

Open identification of one’s sexual orientation may be hindered by homophobia which encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT). It can be expressed as antipathy, contempt, prejudice, aversion, or hatred; it may be based on irrational fear and is sometimes related to religious beliefs (Carroll, 2016). Homophobia is observable in critical and hostile behavior, such as discrimination and violence on the basis of sexual orientations that are non-heterosexual. Recognized types of homophobia include institutionalized homophobia, such as religious and state-sponsored homophobia, and internalized homophobia in which people with same-sex attractions internalize, or believe, society’s negative views and/or hatred of themselves.

Sexual minorities regularly experience stigma, harassment, discrimination, and violence based on their sexual orientation (Carroll, 2016). Research has shown that gay, lesbian, and bisexual teenagers are at a higher risk of depression and suicide due to exclusion from social groups, rejection from peers and family, and negative media portrayals of homosexuals (Bauermeister et al., 2010). Discrimination can occur in the workplace, in housing, at schools, and in numerous public settings. Much of this discrimination is based on stereotypes and misinformation. Major policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation have only come into effect in the United States in the last few years.

The majority of empirical and clinical research on LGBT populations are done with largely white, middle-class, well-educated samples. This demographic limits our understanding of more marginalized sub-populations that are also affected by racism, classism, and other forms of oppression. In the United States, non-Caucasian LGBT individuals may find themselves in a double minority, in which they are not fully accepted or understood by Caucasian LGBT communities and are also not accepted by their own ethnic group (Tye, 2006). Many people experience racism in the dominant LGBT community where racial stereotypes merge with gender stereotypes.

7.3 Cognitive Development in Emerging and Early Adulthood

Distinguish between formal and postformal thought

Describe dialectical thought

Describe the changes in educational attainment and the costs of education

Describe the benefits of education beyond high school

Describe the stages in career development, millennial employment, and NEETS

Describe sexism and how it affects pay, hiring, employment, and education

7.3.1 Beyond Formal Operational Thought: Postformal Thought

As mentioned in chapter 6, according to Piaget’s theory adolescents acquire formal operational thought. The hallmark of this type of thinking is the ability to think abstractly or to consider possibilities and ideas about circumstances never directly experienced. Thinking abstractly is only one characteristic of adult thought, however. If you compare a 15 year-old with someone in their late 30s, you would probably find that the latter considers not only what is possible, but also what is likely. Why the change? The adult has gained experience and understands why possibilities do not always become realities. They learn to base decisions on what is realistic and practical, not idealistic, and can make adaptive choices. Adults are also not as influenced by what others think. This advanced type of thinking is referred to as Postformal Thought (Sinnott, 1998).

Dialectical Thought: In addition to moving toward more practical considerations, thinking in early adulthood may also become more flexible and balanced. Abstract ideas that the adolescent believes in firmly may become standards by which the adult evaluates reality. Adolescents tend to think in dichotomies; ideas are true or false; good or bad; and there is no middle ground. However, with experience, the adult comes to recognize that there is some right and some wrong in each position, some good or some bad in a policy or approach, some truth and some falsity in a particular idea. This ability to bring together salient aspects of two opposing viewpoints or positions is referred to as dialectical thought and is considered one of the most advanced aspects of postformal thinking (Basseches, 1984). Such thinking is more realistic because very few positions, ideas, situations, or people are completely right or wrong. So, for example, parents who were considered angels or devils by the adolescent eventually become just people with strengths and weaknesses, endearing qualities, and faults to the adult.

Does everyone reach postformal or even formal operational thought? Formal operational thought involves being able to think abstractly; however, this ability does not apply to all situations or all adults. Formal operational thought is influenced by experience and education. Some adults lead lives in which they are not challenged to think abstractly about their world. Many adults do not receive any formal education and are not taught to think abstractly about situations they have never experienced. Further, they are also not exposed to conceptual tools used to formally analyze hypothetical situations. Those who do think abstractly may be able to do so more easily in some subjects than others. For example, psychology majors may be able to think abstractly about psychology but be unable to use abstract reasoning in physics or chemistry. Abstract reasoning in a particular field requires a knowledge base we might not have in all areas. Consequently, our ability to think abstractly often depends on our experiences.

7.3.2 Education

According to the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems (NCHEMS) (2016a, 2016b, 2016c, 2016d), in the United States:

84% of 18 to 24 year olds and 88% of those 25 and older have a high school diploma or its equivalent

36% of 18 to 24 year olds and 7% of 25 to 49 year olds attend college

59% of those 25 and older have completed some college

32.5% of those 25 and older have a bachelor’s degree or higher, with slightly more women (33%) than men (32%) holding a college degree (Ryan & Bauman, 2016).

The rate of college attainment has grown more slowly in the United States than in a number of other nations in recent years (OCED, 2014). This may be due to fact that the cost of attaining a degree is higher in the U.S. than in many other nations.

In 2017, 65% of college seniors who graduated from private and public nonprofit colleges had student loan debt, and nationally owed an average of $28,650, a 1% decline from 2016 (The Institute for College Access & Success (TICAS), 2018). See Figure 7.17 for yearly comparisons.

According to the most recent TICAS annual report, the rate of debt varied widely across states, as well as between colleges. The after graduation debt ranged from 18,850 in Utah to $38,500 in Connecticut. Low-debt states are mainly in the West, and high-debt states in the Northeast. In recent years there has been a concern about students carrying more debt and being more likely to default when attending for-profit institutions. In 2016, students at for-profit schools borrowed an average of $39,900, which was 41% higher than students at non-profit schools that year. In addition, 30% of students attending for-profit colleges default on their federal student loans. In contrast, the default level of those who attended public institutions is only 4% (TICAS, 2018).

College student debt has become a key issue at both the state and federal political level, and some states have been taking steps to increase spending and grants to help students with the cost of college. However, 15% of the Class of 2017’s college debt was owed to private lenders (TICAS, 2018). Such debt has less consumer protection, fewer options for repayment, and is typically negotiated at a higher interest rate. See Table 7.1 for a debt comparison of 6 U.S. States.

Graduate School: Larger amounts of student debt actually occur at the graduate level (Kreighbaum, 2019). In 2019, the highest average debts were concentrated in the medical fields. Average median debt for graduate programs included:

$42,335 for a master’s degree

$95,715 for a doctoral degree

$141,000 for a professional degree

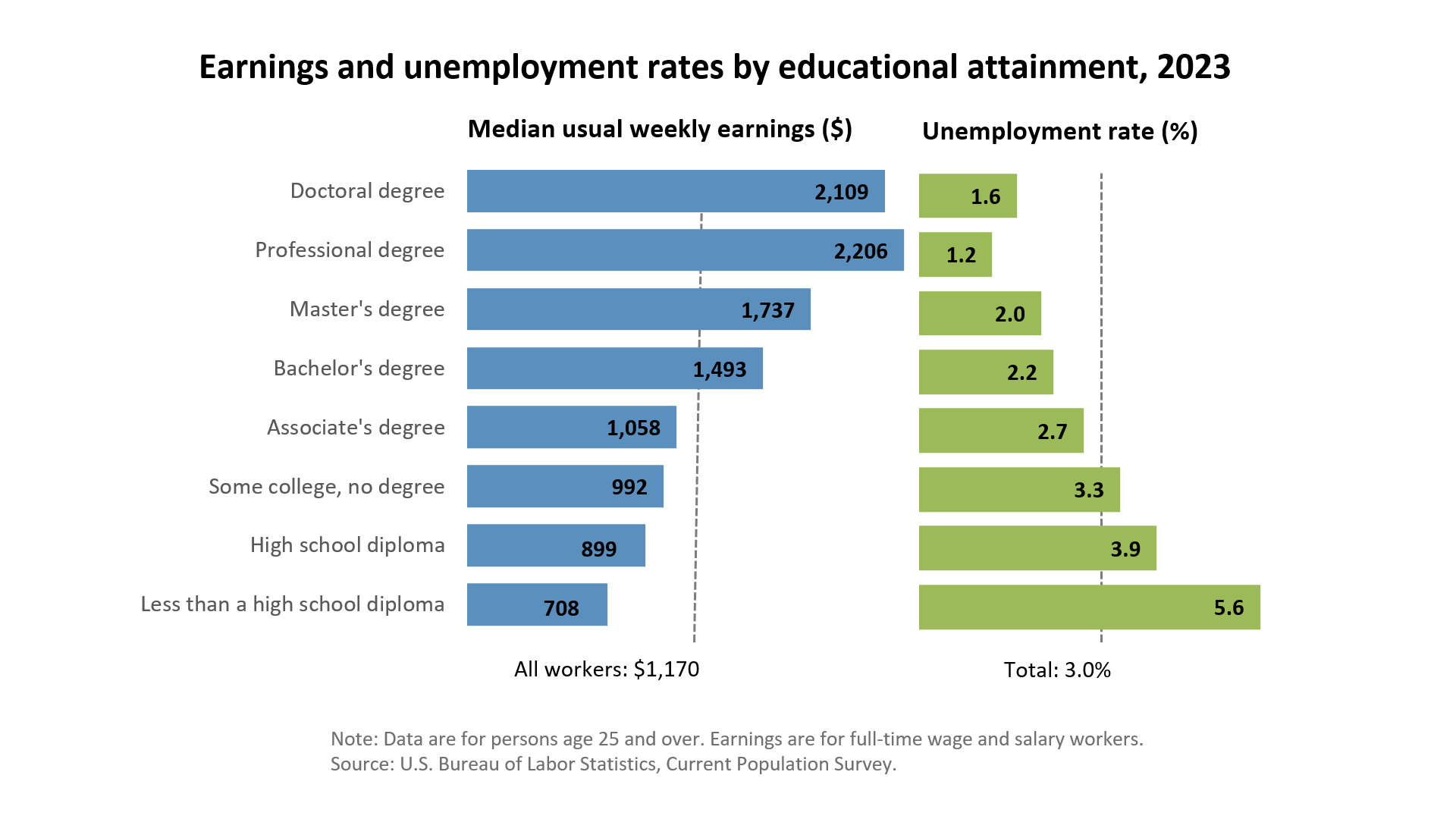

Worldwide, over 80% of college educated adults are employed, compared with just over 70% of those with a high school or equivalent diploma, and only 60% of those with no high school diploma (OECD, 2015). Those with a college degree will earn more over the course of their life time. Moreover, the benefits of college education go beyond employment and finances. The OECD found that around the world, adults with higher educational attainment were more likely to volunteer, felt they had more control over their lives, and thus were more interested in the world around them. Studies of U.S. college students find that they gain a more distinct identity and become more socially competent, less dogmatic and ethnocentric compared to those not in college (Pascarella, 2006).

Is college worth the time and investment? College is certainly a substantial investment each year, with the financial burden falling on students and their families in the U.S., and mainly by the government in many other nations. Nonetheless, the benefits both to the individual and the society outweighs the initial costs. As can be seen in Figure 7.18, those in America with the most advanced degrees earn the highest income and have the lowest unemployment.

7.3.3 Career Development and Employment

Work plays a significant role in the lives of people, and emerging and early adulthood is the time when most of us make choices that will establish our careers. Career development has a number of stages:

Stage One: As children we may select careers based on what appears glamorous or exciting to us (Patton & McMahon, 1999). There is little regard in this stage for whether we are suited for our occupational choices.

Stage Two: In the second stage, teens include their abilities and limitations, in addition to the glamour of the occupation when narrowing their choices.

Stage Three: Older teens and emerging adults narrow their choices further and begin to weigh more objectively the requirements, rewards, and downsides to careers, along with comparing possible careers with their own interests, values, and future goals (Patton & McMahon, 1999). However, some young people in this stage “fall-into” careers simply because these were what were available at the time, because of family pressures to pursue particular paths, or because these were high paying jobs, rather than from an intrinsic interest in that career path (Patton & McMahon, 1999).

Stage Four: Super (1980) suggests that by our mid to late thirties, many adults settle in their careers. Even though they might change companies or move up in their position, there is a sense of continuity and forward motion in their career. However, some people at this point in their working life may feel trapped, especially if there is little opportunity for advancement in a more dead-end job.

How have things changed for Millennials compared with previous generations of early adults? In recent years, young adults are more likely to find themselves job-hopping, and periodically returning to school for further education and retraining than in prior generations. However, researchers find that occupational interests remain fairly stable. Thus, despite the more frequent change in jobs, most people are generally seeking jobs with similar interests rather than entirely new careers (Rottinghaus, Coon, Gaffey & Zytowski, 2007). As of 2016, millennials became the largest generation in the labor force (Fry, 2018) (See Figure 7.19).

Recent research also suggests that Millennials are looking for something different in their place of employment. According to a recent Gallup poll report (2016), Millennials want more than a paycheck, they want a purpose. Unfortunately, only 29% of Millennials surveyed by Gallup reported that they were “engaged” at work. In fact, they report being less engaged than Gen Xers and Baby Boomers; with 55% of Millennials saying they are not engaged at all with their job. This indifference to their workplace may explain the greater tendency to switch jobs. With their current job giving them little reason to stay, they are more likely to take any new opportunity to move on. Only half of Millennials saw themselves working at the same company a year later. Gallup estimates that this employment turnover and lack of engagement costs businesses $30.5 billion a year.

NEETs: Around the world, teens and young adults were some of the hardest hit by the economic downturn in recent years (Desilver, 2016). Consequently, a number of young people have become NEETs, neither employed nor in education or training. While the number of young people who are NEETs has declined more recently, there is concern that “without assistance, economically inactive young people won’t gain critical job skills and will never fully integrate into the wider economy or achieve their full earning potential” (Desilver, 2016, para. 3). In parts of the world where the rates of NEETs are persistently high, there is also concern that having such large numbers of young adults with little opportunity may increase the chances of social unrest.

In the United States, in 2017 over 13% of 15 to 29 year-olds were neither employed nor in school, (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, (OECD), 2019). This is down from 2013, when approximately 18.5% of this age group fit the category (Desilver, 2016). More young women than men in the United States find themselves unemployed and not in school or training for a job. Additionally, most NEETs have high school or less education, and Asians are less likely to be NEETs than any other ethnic group in the US (Desilver, 2016).

The rate of NEETs varies around the world, with higher rates found in nations that have been the hardest hit by economic recessions, and government austerity measures. The number of NEETs also varies widely between the genders, although females are more likely to be NEETs in all nations (see Table 7.1).

| Country | Females | Males | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 12.80 | 9.14 | 10.9 |

| Canada | 11.83 | 12.46 | 12.2 |

| Denmark | 11.86 | 11.67 | 11.8 |

| France | 17.75 | 15.34 | 16.5 |

| Germany | 11.27 | 7.60 | 9.3 |

| Italy | 26.94 | 23.38 | 25.1 |

| Mexico | 34.21 | 7.90 | 21.2 |

| Russia | 16.28 | 8.66 | 12.4 |

| Sweden | 8.42 | 7.69 | 8.0 |

| Turkey | 39.90 | 15.08 | 27.2 |

| United Kingdom | 13.95 | 10.50 | 12.2 |

| United States of America | 15.69 | 10.89 | 13.3 |

What role does gender play on career and employment? Gender also has an impact on career choices. Despite the rise in the number of women who work outside of the home, there are some career fields that are still pursued more by men than women. Jobs held by women still tend to cluster in the service sector, such as education, nursing, and child-care worker. While in more technical and scientific careers, women are greatly outnumbered by men. Jobs that have been traditionally held by women tend to have lower status, pay, benefits, and job security (Bosson, et al., 2019). In recent years, women have made inroads into fields once dominated by males, and today women are almost as likely as men to become medical doctors or lawyers. Despite these changes, women are more likely to have lower-status, and thus less pay than men in these professions. For instance, women are more likely to be a family practice doctor than a surgeon or are less likely to make partner in a law firm (Ceci & Williams, 2007).Sexism

Sexism or gender discrimination is prejudice or discrimination based on a person’s sex or gender (Bosson, Vandello, & Buckner, 2019). Sexism can affect any sex that is marginalized or oppressed in a society; however, it is particularly documented as affecting females. It has been linked to stereotypes and gender roles and includes the belief that males are intrinsically superior to other sexes and genders. Extreme sexism may foster sexual harassment, rape, and other forms of sexual violence.

Sexism can exist on a societal level, such as in hiring, employment opportunities, and education. In the United States, women are less likely to be hired or promoted in male-dominated professions, such as engineering, aviation, and construction (Blau, Ferber, & Winkler, 2010; Ceci & Williams, 2011). In many areas of the world, young girls are not given the same access to nutrition, healthcare, and education as boys. Sexism also includes people’s expectations of how members of a gender group should behave. For example, women are expected to be friendly, passive, and nurturing; when a woman behaves in an unfriendly or assertive manner, she may be disliked or perceived as aggressive because she has violated a gender role (Rudman, 1998). In contrast, a man behaving in a similarly unfriendly or assertive way might be perceived as strong or even gain respect in some circumstances.

Occupational sexism involves discriminatory practices, statements, or actions, based on a person’s sex, that occur in the workplace. One form of occupational sexism is wage discrimination. In 2008, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that while female employment rates have expanded, and gender employment and wage gaps have narrowed nearly everywhere, on average women still have a 20 percent less chance to have a job. The Council of Economic Advisors (2015) found that despite women holding 49.3% of the jobs, they are paid only 78 cents for every $1.00 a man earns. It also found that despite the fact that many countries, including the U.S., have established anti-discrimination laws, these laws are difficult to enforce. A recent example of significant wage inequality occurred among athletes.

2019 Women’s World Cup: The world witnessed the tremendous athleticism and soccer skills demonstrated by female players from 24 different countries during the 2019 Women’s World Cup. Amid the cheering at the end of the final match between the United States and the Netherlands, were chants of “equal pay” (Channick, 2019). Throughout the tournament, attention was focused on the discrepancy between what male soccer players earned compared to the female players. In winning the World Cup, the American women’s team earned $4 million as part of a $30 million prize pool (Peterson, 2019). In contrast, the French men’s team, who won the Men’s World Cup in 2018, earned $38 million as part of the $400 million prize pool. The Federation of Association Football (FIFA) promised to double the prize money to $60 million for the 2023 Women’s World Cup, but that still lags far behind the $440 million that will be given out for the Men’s World Cup in 2022. In the United States, the women’s soccer team generates more revenue and receives higher TV ratings than the men’s team, yet the women get paid significantly less. By winning the 2019 Women’s World Cup, each woman should receive $200,000, yet if the American men had won the 2018 Men’s World Cup, each would have received $1.1 million (Hess, 2019). Because of this discrepancy, in March 2019, 28 members of the women’s team filed a lawsuit against the United States Soccer Federation for gender discrimination and unequal pay (Channick, 2019).

Factors Affecting Wage Inequality: There are many possible explanations for the wage gap. It has been argued in the past that education may account for the wage gap. However, the wage gap exists at every of education level (Bosson et al., 2019). Men with less than high school to men with graduate degree earn more than women with the same level of education. In addition, women now attain more associates, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees than men, and very similar levels of professional degrees and doctorates, according to a recent Census survey (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). As the wage gap still exists in most occupations it cannot be the explanation. Instead, occupational segregation is a likely contributor to the overall wage gap, as women tend to work in very different occupations than men, and those jobs tend to have lower wages. In addition, the entry of women into a field tends to reduce the wages and prestige of the job. Mandel (2013) found that jobs typically held by men who saw the biggest influx of women into those careers, also saw the biggest drop in wages.

Sticky floors, which keep low-wage workers, who are more likely to be women and minorities, from being promoted contribute to lower wages (Bosson, et al. 2019). Women are disproportionately in low-paid occupations, such as clerical, childcare, and service workers (Hegewisch & Ellis, 2015). They also get paid less than men in the same jobs, as can be seen in Table 7.2. This is a list of some of the top jobs held by women (e.g., maid, social worker, nurse) and top jobs held by men (e.g., software developer, janitor, police officer) in the United States. The second column shows women’s earnings as a percentage of the earnings of men in those careers. In only one occupation are women paid more than men on average; stock clerk. Men are not only being paid more in more masculine jobs, but also in jobs typically held by women.

| Occupation | Wage Gap |

| Stock clerk, order filler | 102 |

| Maid, housekeeping cleaner | 99 |

| Social worker | 94.1 |

| Registered nurse | 90.4 |

| Customer service representative | 86.8 |

| Secretary/administrative assistant | 84.5 |

| Software developer | 83.9 |

| Office supervisor | 83 |

| Waitress/waiter | 82.8 |

| Accountant, auditor | 80.8 |

| Janitor, building cleaner | 76.9 |

| Driver/sales worker/truck driver | 73.7 |

| Police and sheriff’s patrol officer | 71.2 |

Other factors include that more than half of men report having negotiated their salary when being hired, compared with 12% of women (Babcock, Gelfand, Small, & Stayn, 2006). However, people perceive women who negotiate more negatively then they do men, as assertive women, but not men, are more likely to be penalized. Women are also more likely to have interruptions in their careers either through the birth of children, or relocation due to a change in their partner’s job. Women are also less likely to relocate for the sake of their families when a better job offer comes along, and employers know this. It has been suggested that one reason why males may be offered more money is to keep them from leaving (Baldridge, Eddleston, & Vega, 2006). Aditionally, men are more likely to work overtime.

Barriers to Positions of Power: There are a few barriers to women achieving positions of power. The glass ceiling is the invisible barrier that keeps women and minorities from rising to higher positions regardless of their qualifications (Bosson et al., 2019). Women hold only 4.5% of CEO positions and 14% of top executive positions around the world (Noland, Moran, & Kotschwar, 2016). In addition, Noland and colleagues found that in a study of nearly 22,000 companies worldwide, in 77% of those firms only 30% of women held an executive position or board seat. There were only 11 companies, or 0.05% of all the firms studied, where women held all the executive positions and board seats. Some researchers see the root cause of this situation in the tacit discrimination based on gender, conducted by current top executives and corporate directors, who are primarily male.

Often the barriers to achieving one’s goals are not obvious. For instance, some argue that the gender role stereotypes cast managerial positions as “masculine”. Unfortunately, when women do rise to positions of power it is often at a time when a company or country is faced with a major crisis. This is called the glass cliff, and it refers to women and minorities being placed in leadership positions when the risk of failure is high. For instance, female lawyers are more likely than their male counterparts to lead a high-risk cases, and female politicians are more likely to be recommended to run in unwinnable seats (Bruckmuller, Ryan, Floor, & Haslam, 2014).

Worldwide Gender Parity: The World Economic Forum (2017) introduced The Global Gender Gap Report in 2006 as way of tracking gender based disparities between men and women in the world. The most recent report in 2017 analyzed 144 countries on gender equality in the areas of: economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment. Countries are then ranked to create global awareness of the challenges posed by gender gaps in different areas of the world. A parity rating of 100% would mean that females and males achieved equality on these measures. Results indicated:

68% gender parity was found worldwide across the four areas. Specifically, there was 96% parity in health outcomes, 95% parity in educational attainment, 58% parity in economic participation, and only 23% parity in political empowerment.

The top spots were held by smaller Western European countries, particularly the Nordic countries as Iceland (88% parity), Norway (83% parity) and Finland (82% parity) occupied the top three positions.

The United States ranked 49th with 72% gender parity.

Following the current trends, it will take 100 years for global gender parity.

Improving gender parity is expected to provide significant economic gains for a country and closing the occupational gender gaps would be one way to achieve this.

7.5 References

Allendorf, K. (2013). Schemas of marital change: From arranged marriages to eloping for love. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 453-469.

Alterovitz, S., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (2011). Partner preferences across the life span: Online dating by older adults. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1(S), 89-95.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (Fifth Edition). Washington, D. C.: Author.

American Psychological Association. (2016). Sexual orientation and homosexuality. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/topics/lgbt/orientation.aspx

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469-480.

Arnett, J. J. (2001). Conceptions of the transitions to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence to midlife. Journal of Adult Development, 8, 133-143.

Arnett, J. J. (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 63–75.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. In J. J. Arnett & N. Galambos (Eds.), Cultural conceptions of the transition to adulthood: New directions in child and adolescent development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Arnett, J. J. (2006). G. Stanley Hall’s adolescence: Brilliance and non-sense. History of Psychology, 9, 186-197.

Arnett, J.J. (2007). The long and leisurely route: Coming of age in Europe today. Current History, 106, 130-136.

Arnett, J. J. (2011). Emerging adulthood(s): The cultural psychology of a new life stage. In L.A. Jensen (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental psychology: New syntheses in theory, research, and policy (pp. 255–275). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2016). Does emerging adulthood theory apply across social classes? National data on a persistent question. Emerging Adulthood, 4(4), 227-235.

Arnett, J. J., & Taber, S. (1994). Adolescence terminable and interminable: When does adolescence end? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 23, 517–537.

Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family relationships and support systems in emerging adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193-217). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Babcock, L., Gelfand, M., Small, D., & Stayn, H. (2006). Gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations. In D. De Cremer, M. Zelenberg, & J.K. Muringham (Eds.), Social psychology and economics (pp. 239-262). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2008). Becoming friends by chance. Psychological Science, 19(5), 439–440.