10 Death and Dying

We have now reached the end of the lifespan. While it is true that death occurs more commonly at the later stages of age, death can occur at any point in the life cycle. Death is a deeply personal experience evoking many different reactions, emotions, and perceptions. Children and young adults in their prime of life may perceive death differently from adults dealing with chronic illness or the increasing frequency of the death of family and friends. If asked, most people envision their death as quick and peaceful. However, except for a handful of illnesses in which death does often quickly follow diagnosis, or in the case of accidents or trauma, most deaths come after a lengthy period of chronic illness or frailty (Institute of Medicine (IOM), 2015). While modern medicine and better living conditions have led to a rise in life expectancy around the world, death will still be the inevitable final chapter of our lives.

10.1 Death and Dying

Define death

Describe what characterizes physical and social death

Compare the leading causes of death in the world with those in the United States

Review the current statistics on suicide and fatal drug overdoses

Define deaths of despair

Explain where people die

Describe how attitudes about death and death anxiety change as people age

Explain the philosophy and practice of palliative care

Describe the roles of hospice and family caregivers

Explain the different types of advanced directives

Describe cultural differences in end of life decisions

Explain the different types of euthanasia and their controversies

Describe funeral rituals in different religions

Describe the new practice of green burials

Differentiate among grief, bereavement, and mourning

List and describe the stages of loss based on Kübler-Ross’s model and describe the criticisms of the mode

Explain the dual-process model of grief

Identify the impact of losing a child and parent

Identify the four tasks of mourning

Explain the importance of support groups for those in grief

10.1.1 Death Defined

One way to understand death and dying is to look more closely at what defines physical death and social death. According to the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) (Uniform Law Commissioners, 1980), death is defined clinically as the following:

An individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, is dead. A determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.

The UDDA was approved for the United States in 1980 by a committee of national commissioners, the American Medical Association, the American Bar Association, and the President’s Commission on Medical Ethics. This act has since been adopted by most states and provides a comprehensive and medically factual basis for determining death in all situations.

Death Process: For those individuals who are terminal, and death is expected, a series of physical changes occur. Bell (2010) identifies some of the major changes that occur in the weeks, days, and hours leading up to death:

Weeks Before Passing

Minimal appetite; prefer easily digested foods

Increase in the need for sleep

Increased weakness

Incontinence of bladder and/or bowel

Restlessness or disorientation

Increased need for assistance with care

Days Before Passing

Decreased level of consciousness

Pauses in breathing

Decreased blood pressure

Decreased urine volume and urine color darkens

Murmuring to people others cannot see

Reaching in air or picking at covers

Need for assistance with all care

Days to Hours Before Passing

Decreased level of consciousness or comatose-like state

Inability to swallow

Pauses in breathing become longer

Shallow breaths

Weak or absent pulse

Knees, feet, and/or hands becoming cool or cold

Knees, feet, and/or hand discoloring to purplish hue

Noisy breathing due to relaxed throat muscles, often called a “death rattle”

Skin coloring becoming pale, waxen (pp. 5, 176-177)

Social death begins much earlier than physical death (Pattison, 1977). Social death occurs when others begin to dehumanize and withdraw from someone who is terminally ill or has been diagnosed with a terminal illness (Glaser & Strauss, 1966). Dehumanization includes ignoring them, talking about them if they were not present, making decisions without consulting them first, and forcing unwanted procedures. Sweeting and Gilhooly (1997) further identified older people in general, and people with a loss of personhood, as having the characteristics necessary to be treated as socially dead. More recently, the concept has been used to describe the exclusion of people with HIV/AIDS, younger people living with terminal illness, and the preference to die at home (Brannelly, 2011). Those diagnosed with conditions such as AIDS or cancer may find that friends, family members, and even health care professionals begin to say less and visit less frequently. Meaningful discussions may be replaced with comments about the weather or other topics of light conversation. Doctors may spend less time with patients after their prognosis becomes poor.

Why do others begin to withdraw? Friends and family members may feel that they do not know what to say or that they can offer no solutions to relieve suffering. They withdraw to protect themselves against feeling inadequate or from having to face the reality of death. Health professionals, trained to heal, may also feel inadequate and uncomfortable facing decline and death. People in nursing homes may live as socially dead for years with no one visiting or calling. Social support is important for quality of life, and those who experience social death are deprived from the benefits that come from loving interaction with others (Bell, 2010).

Why would younger or healthier people dehumanize those who are incapacitated, older, or unwell? One explanation is that dehumanization is the result of the healthier person placing a protective distance between themselves and the incapacitated, older, or unwell person (Brannelly, 2011). This keeps the well person from thinking of themselves as becoming ill or in need of assistance. Another explanation is the repeated experience of loss that paid caregivers experience when working with terminally ill and older people requires a distance which protects against continual grief and sadness, and possibly even burnout.

10.1.2 Most Common Causes of Death

The World: The most recent statistics analyzed by the World Health Organization were in 2016 (WHO, 2018) and non-communicable deaths; that is, those not passed from person-to-person, were responsible for the majority of deaths (see Figure 10.2). The three most common noncommunicable diseases were heart disease, stroke, and COPD. Tobacco use is attributed as one of the top killers and is often the hidden cause behind many of the diseases that result in death, such as heart disease and chronic lung diseases.

These statistics hide the differences in the causes of death among high versus low income nations. In high-income countries, defined as having a per capita annual income of $12,476 or more, 70% of deaths are among people aged 70 and older. Only 1% of deaths occur in children under 15 years of age. People predominantly die of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancers, dementia, or diabetes. Lower respiratory infections remain the only leading infectious cause of death in such nations. In contrast, in low-income countries, defined as having a per capital annual income of $1025 or less, almost 40% of deaths are among children under age 15, and only 20% of deaths are among people aged 70 years and older. People predominantly die of infectious diseases such as lower respiratory infections, HIV/AIDS, diarrheal diseases, malaria and tuberculosis. These account for almost one third of all deaths in these countries. Complications of childbirth due to prematurity, birth asphyxia, and birth trauma are among the leading causes of death for newborns and infants in the poorest of nations (WHO, 2018).

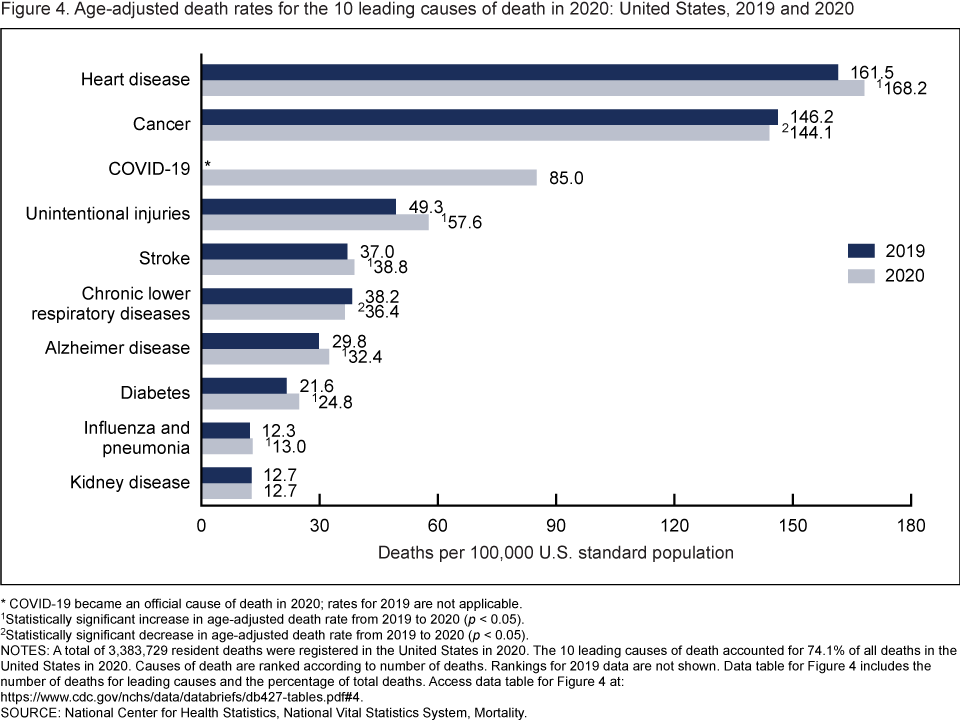

The United States: In 1900, the most common causes of death were infectious diseases, which brought death quickly. Today, the most common causes of death are chronic diseases in which a slow and steady decline in health ultimately results in death. In 2016, heart disease, cancer, and accidents were the leading causes of death (see Figure 10.1, The Advisory Board, 2018).

The causes of death vary by age (see Figure 10.4 and 10.5, Heron, 2018). Prior to age 1, SIDS, congenital problems, and other birth complications are the largest contributors to infant mortality. Accidents, known as unintentional injury, become the leading cause of death throughout childhood and into middle adulthood. In later middle adulthood and late adulthood heart disease, cancer and other medical conditions become the leading killers.

Chapters 8 and 9 discussed the chronic conditions that are associated with dying at later stages in life. However, suicides and drug overdoses are currently claiming lives throughout the lifespan, and consequently will be discussed next.

10.1.3 Suicide

According to the latest research from the CDC (Hedegaard, Curtin, & Warner, 2018), the suicide rate increased 33% from 1999 through 2017. In the United States, suicide is the 10th leading cause of death overall, but it ranks as the 2nd leading cause of death for those 10-34 and the 4th leading cause for those aged 35-54 (Weir, 2019). Overall, approximately 45, 0000 people died by suicide in 2016 (CDC, 2018). Suicide rates have risen for all racial and ethnic groups and increased in every state, except for Nevada which was already high. Further, the suicide rate for the most rural counties (20.0 per 100,000) is higher than the most urban counties (11.1 per 100,000) (Hedegaard et al., 2018).

Suicide and Gender: Suicide rates increased for both males and females, especially after 2006. For males, the rate increased 26% from 17.8 per 100,000 males in 1999 to 22.4 per 100,000 in 2017. For females, the rate increased 53% from 4.0 per 100,000 females in 1999 to 6.1 per 100,000 in 2017 (see Figure 10.6).

By ages, suicide rates for females in 2017 were higher for every age group, except those aged 75 and older. The highest female rates were for those aged 45–64. In contrast, men aged 75 and older had the highest rates, although the rate for older males had decreased from 1999 (see Figures 10.7 and 10.8).

Males have consistently demonstrated higher rates of suicide as they typically experience higher rates of substance use disorders, do not seek out mental health treatment, and use more lethal means. However, females are now closing the suicide gap with males, as females are now responding to the stress in their lives through self-harm, substance abuse, and risk taking behaviors (Healy, 2019). Females who identify pain, depression, and anxiety are especially at risk in middle age.

Deaths of Despair: While the suicide rate has increased in America, during the same period it has gone down in other countries, including Canada, Japan, China, Russia, United Kingdom, Germany, and most of Western Europe. Globally, suicide rates have fallen when the living conditions have improved (Weir, 2019). Not surprisingly, the opposite is true, and thus a decrease in economic and social well-being, referred to as deaths of despair, has been linked to suicides in America. The loss of farming and manufacturing jobs are believed to have contributed to these deaths of despair, especially in rural communities where there is less access to mental health treatment. According to the CDC (2018), other factors that contributed to suicide among those with and without mental health conditions included relationship problems, substance use disorders, financial or legal problems, and health concerns (see Figure 10.9).

Prevention: Globally, limiting access to lethal means has contributed to a decrease in suicide rates (Weir, 2019). For example, switching from less-toxic gas for heating decreased carbon monoxide deaths, making it more difficult to access toxic pesticides decreased poisoning deaths, installing bridge barriers decreased jumping, and limiting access to firearms lowered deaths by guns. Equally as important are prevention programs and improving access to mental health treatment, especially in the workplace. Many occupations have seen increases in suicide rates, and consequently specific programs are being designed to address the stressors associated with these jobs. Knowing the warning signs of suicide and encouraging someone to get treatment are things that everyone can do to address the increase in the suicide rate (see callout below).

Feeling like a burden

Being isolated

Increased anxiety

Feeling trapped or in unbearable pain

Increased substance use

Looking for a way to access lethal means

Increased anger or rage

Extreme mood swings

Expressing hopelessness

Sleeping too little or too much

Talking or posting about wanting to die

Making plans for suicide

10.1.4 Fatal Drug Overdoses

Another factor linked to the deaths of despair has been fatal drug overdoses. In 2017, deaths from fatal drug overdoses in the United States equaled 70,237 (Hedegaard, Miniño, & Warner, 2018). The rate of drug overdose deaths has been steadily increasing since 1999, and in 2017 the rate (21.7/100,000) was 9.6% higher than the rate in 2016 (19.8/100,000) (see Figure 10.11). Unlike suicide rates, deaths from overdoses occur equally among those living in urban and rural areas. The rate of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone (drugs such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol) increased by 45% between 2016 and 2017, from 6.2 to 9.0 per 100,000 (see Figure 10.12). Fetanyl is an especially powerful opioid that can easily lead to a fatal overdose. Because it is synthetic, it is cheap to make and easier to conceal than heroin.

10.1.5 Where do People Die?

Gathering statistics on the location of death is not a simple matter. Those with terminal illnesses may be going through the process of dying at home or in a nursing home, only to be transported to a hospital in the final hours of their life. According to the Stanford Medical School (2019), most Americans (80%) would prefer to die at home, however:

60% of Americans die in acute care hospitals

20% in nursing homes

20% at home.

While dying at home is not favored in certain cultures, and some patients may prefer to die in a hospital, the results indicate that less people are dying at home than want to.

Internationally, 54% of deaths in over 45 nations occurred in hospitals, with the most frequent occurring in Japan (78%) and the least frequent occurring in China (20%), according to a study by Broad et al. (2013). They also found that for older adults, 18% of deaths occurred in some form of residential care, such as nursing homes, and that for each decade after age 65, the rate of dying in a such settings increased 10%. In addition, the number of women dying in residential care was considerably higher than for males.

10.1.6 Developmental Perceptions of Death and Death Anxiety

The concept of death changes as we develop from early childhood to late adulthood. Cognitive development, societal beliefs, familial responsibilities, and personal experiences all shape an individual’s view of death (Batts, 2004; Erber & Szuchman, 2015; National Cancer Institute, 2013).

Infancy: Certainly, infants do not comprehend death, however, they do react to the separation caused by death. Infants separated from their mothers may become sluggish and quiet, no longer smile or coo, sleep less, and develop physical symptoms such as weight loss.

Early Childhood: As you recall from Piaget’s preoperational stage of cognitive development, young children experience difficulty distinguishing reality from fantasy. It is therefore not surprising that young children lack an understanding of death. They do not see death as permanent, assume it is temporary or reversible, think the person is sleeping, and believe they can wish the person back to life. Additionally, they feel they may have caused the death through their actions, such as misbehavior, words, and feelings.

Middle Childhood: Although children in middle childhood begin to understand the finality of death, up until the age of 9 they may still participate in magical thinking and believe that through their thoughts they can bring someone back to life. They also may think that they could have prevented the death in some way, and consequently feel guilty and responsible for the death.

Late Childhood: At this stage, children understand the finality of death and know that everyone will die, including themselves. However, they may also think people die because of some wrong doing on the part of the deceased. They may develop fears of their parents dying and continue to feel guilty if a loved one dies.

Adolescence: Adolescents understand death as well as adults. With formal operational thinking, adolescents can now think abstractly about death, philosophize about it, and ponder their own lack of existence. Some adolescents become fascinated with death and reflect on their own funeral by fantasizing on how others will feel and react. Despite a preoccupation with thoughts of death, the personal fable of adolescence causes them to feel immune to the death. Consequently, they often engage in risky behaviors, such as substance use, unsafe sexual behavior, and reckless driving thinking they are invincible.

Early Adulthood: In adulthood, there are differences in the level of fear and anxiety concerning death experienced by those in different age groups. For those in early adulthood, their overall lower rate of death is a significant factor in their lower rates of death anxiety. Individuals in early adulthood typically expect a long life ahead of them, and consequently do not think about, nor worry about death.

Middle Adulthood: Those in middle adulthood report more fear of death than those in either early and late adulthood. The caretaking responsibilities for those in middle adulthood is a significant factor in their fears. As mentioned previously, middle adults often provide assistance for both their children and parents, and they feel anxiety about leaving them to care for themselves.

Late Adulthood: Contrary to the belief that because they are so close to death, they must fear death, those in late adulthood have lower fears of death than other adults. Why would this occur? First, older adults have fewer caregiving responsibilities and are not worried about leaving family members on their own. They also have had more time to complete activities they had planned in their lives, and they realize that the future will not provide as many opportunities for them. Additionally, they have less anxiety because they have already experienced the death of loved ones and have become accustomed to the likelihood of death. It is not death itself that concerns those in late adulthood; rather, it is having control over how they die.

10.1.7 Curative, Palliative, and Hospice Care

When individuals become ill, they need to make choices about the treatment they wish to receive. One’s age, type of illness, and personal beliefs about dying affect the type of treatment chosen (Bell, 2010).

Curative care is designed to overcome and cure disease and illness (Fox, 1997). Its aim is to promote complete recovery, not just to reduce symptoms or pain. An example of curative care would be chemotherapy. While curing illness and disease is an important goal of medicine, it is not its only goal. As a result, some have criticized the curative model as ignoring the other goals of medicine, including preventing illness, restoring functional capacity, relieving suffering, and caring for those who cannot be cured.

Palliative care focuses on providing comfort and relief from physical and emotional pain to patients throughout their illness, even while being treated (NIH, 2007). In the past, palliative care was confined to offering comfort for the dying. Now it is offered whenever patients suffer from chronic illnesses, such as cancer or heart disease (IOM, 2015). Palliative care is also part of hospice programs.

Hospice emerged in the United Kingdom in the mid-20th century as a result of the work of Cicely Saunders. This approach became popularized in the U.S. by the work of Elizabeth Kübler-Ross (IOM, 2015), and by 2012 there were 5,500 hospice programs in the U.S. (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), 2013).

Hospice care whether at home, in a hospital, nursing home, or hospice facility involves a team of professionals and volunteers who provide terminally ill patients with medical, psychological, and spiritual support, along with support for their families (Shannon, 2006). The aim of hospice is to help the dying be as free from pain as possible, and to comfort both the patients and their families during a difficult time.

In order to enter hospice, a patient must be diagnosed as terminally ill with an anticipated death within 6 months (IOM, 2015). The patient is allowed to go through the dying process without invasive treatments. Hospice workers try to inform the family of what to expect and reassure them that much of what they see is a normal part of the dying process.

According to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2019) there are four types of hospice care in America:

Routine hospice care, where the patient has chosen to receive hospice care at home, is the most common form of hospice.

Continuous home care is predominantly nursing care, with caregiver and hospice aides supplementing this care, to manage pain and acute symptom crises for 8 to 24 hours in the home.

Inpatient respite care is provided by a hospital, hospice, or long-term care facility to provide temporary relief for family caregivers.

General inpatient care is provided by a hospital, hospice, or long-term care facility when pain and acute symptom management can on be handled in other settings.

In 2017, an estimated 1.5 million people resideing in American received hospice care (NHPCO, 2019). The majority of patients on hospice were patients suffering from dementia, heart disease, or cancer, and typically did not enter hospice until the last few weeks prior to death. Almost one out of three patients were on hospice for less than a week.

According to Shannon (2006), the basic elements of hospice include:

Care of the patient and family as a single unit

Pain and symptom management for the patient

Having access to day and night care

Coordination of all medical services

Social work, counseling, and pastoral services

Bereavement counseling for the family up to one year after the patient’s death

Although hospice care has become more widespread, these new programs are subjected to more rigorous insurance guidelines that dictate the types and amounts of medications used, length of stay, and types of patients who are eligible to receive hospice care (Weitz, 2007). Thus, more patients are being served, but providers have less control over the services they provide, and lengths of stay are more limited. In addition, a recent report by the Office of the Inspector General at U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2018) highlighted some of the vulnerabilities of the hospice system in the U.S. Among the concerns raised were that hospices did not always provide the care that was needed and sometimes the quality of that care was poor, even at Medicare certified facilities.

Not all racial and ethnic groups feel the same way about hospice care. African-American families may believe that medical treatment should be pursued on behalf of an ill relative as long as possible and that only God can decide when a person dies. Chinese-American families may feel very uncomfortable discussing issues of death or being near the deceased family member’s body. The view that hospice care should always be used is not held by everyone, and health care providers need to be sensitive to the wishes and beliefs of those they serve (Coolen, 2012).

10.1.8 Family Caregivers

According to the Institute of Medicine (2015), it is estimated that 66 million Americans, or 29% of the adult population, are caregivers for someone who is dying or chronically ill. Two-thirds of these caregivers are women. This care takes its toll physically, emotionally, and financially. Family caregivers may face the physical challenges of lifting, dressing, feeding, bathing, and transporting a dying or ill family member. They may worry about whether they are performing all tasks safely and properly, as they receive little training or guidance. Such caregiving tasks may also interfere with their ability to take care of themselves and meet other family and workplace obligations. Financially, families may face high out of pocket expenses (IOM, 2015).

As can be seen in Table 10.1, most family caregivers are providing care by themselves with little professional intervention, are employed, and have provided care for more than 3 years. The annual loss of productivity in the U.S. was $25 billion in 2013 as a result of work absenteeism due to providing this care. As the prevalence of chronic disease rises, the need for family caregivers is growing. Unfortunately, the number of potential family caregivers is declining as the large baby boomer generation enters into late adulthood (Redfoot, Feinberg, & Houser, 2013).

| Characteristic | Percentages |

|---|---|

| No home visits by health care professionals | 69% |

| Caregivers are also employed | 72% |

| Duration of employed workers who have been caregiving for 3+ years | 55% |

| Caregivers for the elderly | 67% |

10.1.9 Advanced Directives

Advanced care planning refers to all documents that pertain to end-of-life care. These include advance directives and medical orders. Advance directives include documents that mention a health care agent and living wills. These are initiated by the patient. Living wills are written or video statements that outline the health care initiates the person wishes under certain circumstances. Durable power of attorney for health care names the person who should make health care decisions in the event that the patient is incapacitated. In contrast, medical orders are crafted by a medical professional on behalf of a seriously ill patient. Unlike advanced directives, as these are doctor’s orders, they must be followed by other medical personnel. Medical orders include Physician Orders for Life-sustaining Treatment (POLST), do-not-resuscitate, do-not-incubate, or do-not-hospitalize. In some instances, medical orders may be limited to the facility in which they were written. Several states have endorsed POLST so that they are applicable across heath care settings (IOM, 2015).

Despite the fact that many Americans worry about the financial burden of end-of-life care, “more than one-quarter of all adults, including those aged 75 and older, have given little or no thought to their end-of-life wishes, and even fewer have captured those wishes in writing or through conversation” (IOM, 2015, p. 18).

10.1.10 Cultural Differences in End-of-Life Decisions

Cultural factors strongly influence how doctors, other health care providers, and family members communicate bad news to patients, the expectations regarding who makes the health care decisions, and attitudes about end-of-life care (Ganz, 2019; Searight & Gafford, 2005a). In Western medicine, doctors take the approach that patients should be told the truth about their health. Blank (2011) reports that 75% of the world’s population do not conduct medicine by the same standards. Thus, outside Western nations, and even among certain racial and ethnic groups within the those nations, doctors and family members may conceal the full nature of a terminal illness, as revealing such information is viewed as potentially harmful to the patient, or at the very least is seen as disrespectful and impolite. Chattopadhyay and Simon (2008) reported that in India doctors routinely abide by the family’s wishes and withhold information from the patient, while in Germany doctors are legally required to inform the patient. In addition, many doctors in Japan and in numerous African nations used terms such as “mass,” “growth,” and “unclean tissue” rather than referring to cancer when discussing the illness to patients and their families (Holland, Geary, Marchini, &Tross, 1987). Family members also actively protect terminally ill patients from knowing about their illness in many Hispanic, Chinese, and Pakistani cultures (Kaufert & Putsch, 1997; Herndon & Joyce, 2004).

In western medicine, we view the patient as autonomous in health care decisions (Chattopadhyay & Simon, 2008; Searight & Gafford, 2005a). However, in other nations the family or community plays the main role, or decisions are made primarily by medical professionals, or the doctors in concert with the family make the decisions for the patient. For instance, in comparison to European Americans and African Americans, Koreans and Mexican-Americans are more likely to view family members as the decision makers rather than just the patient (Berger, 1998; Searight & Gafford, 2005a). In many Asian cultures, illness is viewed as a “family event”, not just something that impacts the individual patient (Blank, 2011; Candib, 2002; Chattopadhyay & Simon, 2008). Thus, there is an expectation that the family has a say in the health care decisions. As many cultures attribute high regard and respect for doctors, patients and families may defer some of the end-of-life decision making to the medical professionals (Searight & Gafford, 2005b).

The notion of advanced directives hold little or no relevance in many cultures outside of western society (Blank, 2011). For instance, in India advanced directives are virtually non-existent, while in Germany they are regarded as a major part of health care (Chattopadhyay & Simon, 2008). Moreover, end-of-life decisions involve how much medical aid should be used. In the United States, Canada, and most European countries artificial feeding is more commonly used once a patient has stopped eating, while in many other nations lack of eating is seen as a sign, rather than a cause, of dying and do not consider using a feeding tube (Blank, 2011).

According to a Pew Research Center Survey (Lipka, 2014), while death may not be a comfortable topic to ponder, 37% of their survey respondents had given a great deal of thought about their end-of-life wishes, with 35% having put these in writing. Yet, over 25% had given no thought to this issue. Lipka (2014) also found that there were clear racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life wishes (see Figure 10.18). Whites are more likely than Blacks and Hispanics to prefer to have treatment stopped if they have a terminal illness. While the majority of Blacks (61%) and Hispanics (55%) prefer that everything be done to keep them alive. Searight and Gafford (2005a) suggest that the low rate of completion of advanced directives among non-whites may reflect a distrust of the U.S. health care system as a result of the health care disparities non-whites have experienced. Among Hispanics, patients may also be reluctant to select a single family member to be responsible for end-of-life decisions out of a concern of isolating the person named and of offending other family members, as this is commonly seen as a “family responsibility” (Morrison, Zayas, Mulvihill, Baskin, & Meier, 1998).

10.1.11 Euthanasia

Euthanasia is defined as intentionally ending one’s life when suffering from a terminal illness or severe disability (Youdin, 2016). Euthanasia is further separated into active euthanasia, which is intentionally causing death, usually through a lethal dose of medication, and passive euthanasia occurs when life-sustaining support is withdrawn. This can occur through the removal of a respirator, feeding tube, or heart-lung machine.

Physician-assisted dying is a form of active euthanasia whereby a physician prescribes the means by which a person can die. The United States federal government does not legislate physician-assisted dying as laws are handled at the state level (ProCon.org, 2018). Nine states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) currently allow physician-assisted dying. The person seeking physician-assisted dying must be: (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) have six or less months until expected death, and (3) obtain two oral (or least 15 days apart) and one written request from a physician (ProCon.org, 2016). Table 10.2 lists the 9 states and D.C. that allow physician-assisted dying and the date the act was passed.

| State | Date Passed |

|---|---|

| Oregon | Passed November 8, 1994, but enacted October 27, 1997 |

| Washington | November 4, 2008 |

| Montana | December 31, 2009 |

| Vermont | May 20, 2013 |

| California | September 11, 2015 |

| D.C. | October 5, 2016 |

| Colorado | November 8, 2016 |

| Hawaii | April 5, 2018 |

| New Jersey | March 25, 2019 |

| Maine | June 12, 2019 |

Since 1997 in Oregon, 2,216 people had lethal prescriptions written and 1459 patients (65.8%) died from the medication as of January 2019 (Death with Dignity, 2019) (see Figure 10.19).

Canada and several European countries, including Switzerland, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands also allow physician-assisted dying. As of 2014, Belgium is the only country that allows the right to die to those under the age of 18. Stricter conditions were put in place for children, including parental consent, the child must be suffering from a serious and incurable disease, the child must understand what euthanasia means, and the child’s death must be expected in the near future (Narayan, 2016).

The practice of physician-assisted dying is certainly controversial with religious, legal, ethical, and medical experts weighing in with opinions. The main areas where there is disagreement between those who support physician-assisted dying and those who do not include: (1) whether a person has the legal right to die, (2) whether active euthanasia would become a “slippery slope” and start a trend to legalize deaths for individuals who may be disabled or unable to give consent, (3) how to interpret the Hippocratic Oath and what it exactly means for physicians to do no harm, (4) whether the government should be involved in end-of-life decisions, and (5) specific religious restrictions against deliberately ending a life (ProCon.org, 2016). Not surprisingly, there are strong opinions on both sides of this topic. According to a 2013 Pew Research Center survey, 47% of Americans approve and 49% disapprove of laws that would allow a physician to prescribe lethal doses of drugs that a terminally ill patient could use to commit suicide (Pew Research Center, 2013). Attitudes on physician-assisted dying were roughly the same in 2005, when 46% approved and 45% disapproved.

10.1.12 Religious Practices after Death

Funeral rites are expressions of loss that reflect personal and cultural beliefs about the meaning of death and the afterlife. Ceremonies provide survivors a sense of closure after a loss. These rites and ceremonies send the message that the death is real and allow friends and loved ones to express their love and duty to those who die. Under circumstances in which a person has been lost and presumed dead or when family members were unable to attend a funeral, there can continue to be a lack of closure that makes it difficult to grieve and to learn to live with loss. Although many people are still in shock when they attend funerals, the ceremony still provides a marker of the beginning of a new period of one’s life as a survivor. The following are some of the religious practices regarding death, however, individual religious interpretations and practices may occur (Dresser & Wasserman, 2010; Schechter, 2009).

Hindu: The Hindu belief in reincarnation accelerates the funeral ritual, and deceased Hindus are cremated as soon as possible. After being washed, the body is anointed, dressed, and then placed on a stand decorated with flowers ready for cremation. Once the body has been cremated, the ashes are collected and, if possible, dispersed in one of India’s holy rivers.

Judaism: Among the Orthodox, the deceased is first washed and then wrapped in a simple white shroud. Males are also wrapped in their prayer shawls. Once shrouded the body is placed into a plain wooden coffin. The burial must occur as soon as possible after death, and a simple service consisting of prayers and a eulogy is given. After burial the family members typically gather in one home, often that of the deceased, and receive visitors. This is referred to as “sitting shiva”.

Muslim: In Islam the deceased are buried as soon as possible, and it is a requirement that the community be involved in the ritual. The individual is first washed and then wrapped in a plain white shroud called a kafan. Next, funeral prayers are said followed by the burial. The shrouded dead are placed directly in the earth without a casket and deep enough not to be disturbed. They are also positioned in the earth, on their right side, facing Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

Roman Catholic: Before death an ill Catholic individual is anointed by a priest, commonly referred to as the Anointing of the Sick. The priest recites a prayer and applies consecrated oil to the forehead and hands of the ill person. The individual also takes a final communion consisting of consecrated bread and wine. The funeral rites consist of three parts. First is the wake that usually occurs in a funeral parlor. The body is present, and prayers and eulogies are offered by family and friends. The funeral mass is next which includes an opening prayer, bible readings, liturgy, communion, and a concluding rite. The funeral then moves to the cemetery where a blessing of the grave, scripture reading, and prayers conclude the funeral ritual.

10.1.13 Green Burial

In 2017, the median cost of an adult funeral with viewing and burial was $8,775. The median cost for viewing and cremation was $6,260 (National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA), 2019). The same NFDA survey found that nearly half of all respondents had attended a funeral in a non-traditional setting, such as an outdoor setting that was meaningful to the deceased, and over half of the respondents said they would be interested in exploring green funeral options (NFDA, 2017).

According to the Green Burial Council (GBC) (2019) Americans bury over 64 thousand tons of steel, 17 thousand tons of copper and bronze, 1.6 million tons of concrete, 20 million feet of wood, and over 4 million gallons of embalming fluid every year. As a result, there has been a growing interest in green or natural burials. Green burials attempt to reduce the impact on the environment at every stage of the funeral. This can include using recycled paper, biodegradable caskets, cotton shroud in the place of any casket, formaldehyde free, or no embalming, and trying to maintain the natural environment around the burial site (GBC, 2019). According to the NFDA (2017), many cemeteries have reported that consumers are requesting green burial options, and since many of the add-ons of a traditional burial, such as a concrete vault, embalming, and casket are not required, the cost can be substantially less.

10.1.14 Grief, Bereavement, and Mourning

The terms grief, bereavement, and mourning are often used interchangeably, however, they have different meanings. Grief is the normal process of reacting to a loss. Grief can be in response to a physical loss, such as a death, or a social loss including a relationship or job. Bereavement is the period after a loss during which grief and mourning occurs. The time spent in bereavement for the loss of a loved one depends on the circumstances of the loss and the level of attachment to the person who died. Mourning is the process by which people adapt to a loss. Mourning is greatly influenced by cultural beliefs, practices, and rituals (Casarett, Kutner, & Abrahm,2001).

Grief Reactions: Typical grief reactions involve mental, physical, social and/or emotional responses. These reactions can include feelings of numbness, anger, guilt, anxiety, sadness and despair. The individual can experience difficulty concentrating, sleep and eating problems, loss of interest in pleasurable activities, physical problems, and even illness. Research has demonstrated that the immune systems of individuals grieving is suppressed and their healthy cells behave more sluggishly, resulting in greater susceptibility to illnesses (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010). However, the intensity and duration of typical grief symptoms do not match those usually seen in severe grief reactions, and symptoms typically diminish within 6-10 weeks (Youdin, 2016).

Complicated Grief: After the loss of a loved one, however, some individuals experience complicated grief, which includes atypical grief reactions (Newson, Boelen, Hek, Hofman, & Tiemeier, 2011). Symptoms of complicated grief include: Feelings of disbelief, a preoccupation with the dead loved one, distressful memories, feeling unable to move on with one’s life, and a yearning for the deceased. Additionally, these symptoms may last six months or longer and mirror those seen in major depressive disorder (Youdin, 2016).

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), distinguishing between major depressive disorder and complicated grief requires clinical judgment. The psychologist needs to evaluate the client’s individual history and determine whether the symptoms are focused entirely on the loss of the loved one and represent the individual’s cultural norms for grieving, which would be acceptable. Those who seek assistance for complicated grief usually have experienced traumatic forms of bereavement, such as unexpected, multiple and violent deaths, or those due to murders or suicides (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010).

Disenfranchised Grief: Grief that is not socially recognized is referred to as disenfranchised grief (Doka, 1989). Examples of disenfranchised grief include death due to AIDS, the suicide of a loved one, perinatal deaths, abortions, the death of a pet, lover, or ex-spouse, and psychological losses, such as a partner developing Alzheimer’s disease. Due to the type of loss, there is no formal mourning practices or recognition by others that would comfort the grieving individual. Consequently, individuals experiencing disenfranchised grief may suffer intensified symptoms due to the lack of social support (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010).

Anticipatory Grief: Grief that occurs when a death is expected, and survivors have time to prepare to some extent before the loss is referred to as anticipatory grief. This expectation can make adjustment after a loss somewhat easier (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). A death after a long-term, painful illness may bring family members a sense of relief that the suffering is over, and the exhausting process of caring for someone who is ill is also completed.

10.1.15 Models of Grief

There are several theoretical models of grief, however, none is all encompassing (Youdin, 2016). These models are merely guidelines for what an individual may experience while grieving. However, if individuals do not fit a model, it does not mean there is something “wrong” with the way they experience grief. It is important to remember that there is no one way to grieve, and people move through a variety of stages of grief in various ways.

Five Stages of Grief: Kübler-Ross (1969, 1975) describes five stages of loss experienced by someone who faces the news of their impending death. These “stages” are not really stages that a person goes through in order or only once; nor are they stages that occur with the same intensity. Indeed, the process of death is influenced by a person’s life experiences, the timing of their death in relation to life events, the predictability of their death based on health or illness, their belief system, and their assessment of the quality of their own life. Nevertheless, these stages help us to understand and recognize some of what a dying person experiences psychologically, and by understanding, we are more equipped to support that person as they die.

Denial is often the first reaction to overwhelming, unimaginable news. Denial, or disbelief or shock, protects us by allowing such news to enter slowly and to give us time to come to grips with what is taking place. The person who receives positive test results for life-threatening conditions may question the results, seek second opinions, or may simply feel a sense of disbelief psychologically even though they know that the results are true.

Anger also provides us with protection in that being angry energizes us to fight against something and gives structure to a situation that may be thrusting us into the unknown. It is much easier to be angry than to be sad, in pain, or depressed. It helps us to temporarily believe that we have a sense of control over our future and to feel that we have at least expressed our rage about how unfair life can be. Anger can be focused on a person, a health care provider, at God, or at the world in general. It can be expressed over issues that have nothing to do with our death; consequently, being in this stage of loss is not always obvious.

Bargaining involves trying to think of what could be done to turn the situation around. Living better, devoting self to a cause, being a better friend, parent, or spouse, are all agreements one might willingly commit to if doing so would lengthen life. Asking to just live long enough to witness a family event or finish a task are examples of bargaining.

Depression or sadness is appropriate for such an event. Feeling the full weight of loss, crying, and losing interest in the outside world is an important part of the process of dying. This depression makes others feel very uncomfortable and family members may try to console their loved one. Sometimes hospice care may include the use of antidepressants to reduce depression during this stage.

Acceptance involves learning how to carry on and to incorporate this aspect of the life span into daily existence. Reaching acceptance does not in any way imply that people who are dying are happy about it or content with it. It means that they are facing it and continuing to make arrangements and to say what they wish to say to others. Some terminally ill people find that they live life more fully than ever before after they come to this stage.

According to Kübler-Ross (1969), behind these five stages focused on the identified emotions, there is a sense of hope. Kübler-Ross noted that in all the 200 plus patients she and her students interviewed, a little bit of hope that they might not die was always in the back of their minds.

Criticisms of Kübler-Ross’s Five Stages of Grief: Some researchers have been skeptical of the validity of there being stages to grief among the dying (Friedman & James, 2008). As Kübler-Ross notes in her own work, it is difficult to empirically test the experiences of the dying. “How do you do research on dying,…? When you cannot verify your data and cannot set up experiments?” (Kübler-Ross, 1969, p. 19). She and four students from the Chicago Theology Seminary in 1965 decided to listen to the experiences of dying patients, but her ideas about death and dying are based on the interviewers’ collective “feelings” about what the dying were experiencing and needed (Kübler-Ross, 1969). While she goes on to say in support of her approach that she and her students read nothing about the prior literature on death and dying, so as to have no preconceived ideas, a later work revealed that her own experiences of grief from childhood undoubtedly colored her perceptions of the grieving process (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). Kübler-Ross is adamant in her theory that the one stage that all those who are dying go through is anger. It is clear from her 2005 book that anger played a central role in “her” grief and did so for many years (Friedman & James, 2008).

There have been challenges to the notion that denial and acceptance are beneficial to the grieving process (Telford, Kralik, & Koch, 2006). Denial can become a barrier between the patient and health care specialists and reduce the ability to educate and treat the patient. Similarly, acceptance of a terminal diagnosis may also lead patients to give up and forgo treatments to alleviate their symptoms. In fact, some research suggests that optimism about one’s prognosis may help in one’s adjustment and increase longevity (Taylor, Kemeny, Reed, Bower & Gruenewald, 2000).

A third criticism is not so much of Kübler-Ross’s work, but how others have assumed that these stages apply to anyone who is grieving. Her research focused only on those who were terminally ill. This does not mean that others who are grieving the loss of someone would necessarily experience grief in the same way. Friedman and James (2008) and Telford et al. (2006) expressed concern that mental health professionals, along with the general public, may assume that grief follows a set pattern, which may create more harm than good.

Lastly, the Yale Bereavement Study, completed between January 2000 and January 2003, did not find support for Kübler-Ross’s five stage theory of grief (Maciejewski, Zhang, Block, & Prigerson, 2007). Results indicated that acceptance was the most commonly reported reaction from the start, and yearning was the most common negative feature for the first two years. The other variables, such as disbelief, depression, and anger, were typically absent or minimal.

Although there is criticism of the Five Stages of Grief Model, Kübler-Ross made people more aware of the needs and concerns of the dying, especially those who were terminally ill. As she notes,

…when a patient is severely ill, he is often treated like a person with no right to an opinion. It is often someone else who makes the decision if and when and where a patient should be hospitalized. It would take so little to remember that the sick person has feelings, has wishes and opinions, and has – most important of all – the right to be heard. (1969, p. 7-8).

Dual-Process Model of Grieving: The dual-process model takes into consideration that bereaved individuals move back and forth between grieving and preparing for life without their loved one (Stroebe & Schut, 2001; Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2005). This model focuses on a loss orientation, which emphasizes the feelings of loss and yearning for the deceased and a restoration orientation, which centers on the grieving individual reestablishing roles and activities they had prior to the death of their loved one. When oriented toward loss grieving individuals look back, and when oriented toward restoration they look forward. As one cannot look both back and forward at the same time, a bereaved person must shift back and forth between the two. Both orientations facilitate normal grieving and interact until bereavement has completed.

10.1.16 Grief: Loss of Children and Parents

Loss of a Child: According to Parkes and Prigerson (2010), the loss of a child at any age is considered “the most distressing and long-lasting of all griefs” (p. 142). Bereaved parents suffer an increased risk to both physical and mental health and exhibit an increased mortality rate. Additionally, they earn higher scores on inventories of grief compared to other types of bereavement. Of those recently diagnosed with depression, a high percentage had experienced the death of child within the preceding six months, and 8 percent of women whose child had died attempted or committed suicide. Archer (1999) found that the intensity of grief increased with the child’s age until the age of 17, when it declined. Archer explained that women have a greater chance of having another child when younger, and thus with added age comes greater grief as fertility declines. Certainly, the older the child the more the mother has bonded with the child and will experience greater grief.

Even when children are adults, parents may experience intense grief, especially when the death is sudden. Adult children dying in traffic accidents was associated with parents experiencing more intense grief and depression, greater symptoms on a health check list, and more guilt than those parents whose adult children died from cancer (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010). Additionally, the deaths of unmarried adult children still residing at home and those who experienced alcohol and relationship problems were especially difficult for parents. Overall, in societies in which childhood deaths are statistically infrequent, parents are often unprepared for the loss of their daughter or son and suffer high levels of grief.

Loss of Parents in Adulthood: In contrast to the loss of a child, the loss of parents in adult life is much more common and results in less suffering. In their literature review, Moss and Moss (1995) found that the loss of a parent in adult life is “rarely pathological.” Those adult children who appear to have the most difficulty dealing with the loss of a parent are adult men who remain unmarried and continue to live with their mothers. In contrast, those who are in satisfying marriages are less likely to require grief assistance (Parkes & Prigerson, 2010). To determine the effects of gender on parental death, Marks, Jun and Song (2007) analyzed longitudinal data from the National Survey of Families and Households that assessed multiple dimensions of psychological well-being in adulthood including depression, happiness, self-esteem, mastery, psychological wellness, alcohol abuse, and physical health. Findings indicated that a father’s death led to more negative effects for sons than daughters, and a mother’s death lead to more negative effects for daughters.

Loss of Parents in Childhood: Parental deaths in childhood have been associated with adjustment problems that may last into adulthood. Ellis, Dowrick and Lloyd-Williams (2013) identified several negative outcomes associated with childhood grief including increased chance of substance abuse, greater susceptibility to depression, higher chance of criminal behavior, school underachievement, and lower employment rates. Typically, professional help is not required in helping children and teens who are dealing with the death of a loved one.

However, Worden (2002) identified ten “red flags” displayed by grieving children that may indicate the need for professional assistance:

Persistent difficulty in talking about the dead person

Persistent or destructive aggressive behavior

Persisting anxiety, clinging, or fears

Somatic complaints (stomachaches, headaches)

Sleeping difficulties

Eating disturbance

Marked social withdrawal

School difficulties or serious academic reversal

Persistent self-blame or guilt

Self-destructive behavior

As parents may also be dealing with funeral arrangements and other end of life matters, they may not always have the time to address questions and concerns that children may have. When explaining death to children it is important to use real words, such as died and death (Dresser & Wasserman, 2010). Children do not understand the meanings of such phrases as “passed away”, “left us”, or “lost”, and they can become confused as to what happened. Saying a loved one died of a disease called cancer, is preferable to saying he was “very sick”. The child may become worried when others become sick that they too will die. Consequently, it is important that children have someone who will listen to, and accurately address their concerns.

10.1.17 Mourning

As a society, are we given the tools and time to adequately mourn? Not all researchers agree that we do. The “death-denying, grief-dismissing world” is the modern world (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005, p. 205). We often grieve privately, quickly, and medicate our suffering with substances or activities. Employers grant 3 to 5 days for bereavement, if the loss is that of an immediate family member, and such leaves are sometimes limited to no more than one per year. Yet grief takes much longer and the bereaved are seldom ready to perform well on the job after just a few days. Obviously, life does have to continue, but we need to acknowledge and make more caring accommodations for those who are in grief.

Four Tasks of Mourning: Worden (2008) identified four tasks that facilitate the mourning process. Worden believes that all four tasks must be completed, but they may be completed in any order and for varying amounts of time. These tasks include:

Acceptance that the loss has occurred

Working through the pain of grief

Adjusting to life without the deceased

Starting a new life while still maintaining a connection with the deceased

Support Groups: Support groups are helpful for grieving individuals of all ages, including those who are sick, terminal, caregiving, or mourning the loss of a loved one. Support groups reduce isolation, connect individuals with others who have similar experiences, and offer those grieving a place to share their pain and learn new ways of coping (Lynn & Harrold, 2011). Support groups are available through religious organizations, hospitals, hospice, nursing homes, mental health facilities, and schools for children.

Viewing death as an integral part of the lifespan will benefit those who are ill, those who are bereaved, and all of us as friends, caregivers, partners, family members and humans in a global society.

10.2 References

Advisory Board. (2019). How Americans die. Retrieved from: https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2019/01/16/deaths

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Archer, J. (1999). The nature of grief: The evolution and psychology of reactions to loss. London and New York: Routledge.

Batts, J. (2004). Death and grief in the family: Tips for parents. Retrieved from https://www.nasponline.org/search/search-results?keywords=death+and+grief+in+the+family

Bell, K. W. (2010). Living at the end of life. New York: Sterling Ethos.

Berger, J. T. (1998). Cultural discrimination in mechanisms for health decisions: A view from New York. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 9, 127-131.

Blank, R.H. (2011). End of life decision making across cultures. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 39(2), 201–214.

Brannely, T. (2011). Sustaining citizenship: People with dementia and the phenomenon of social death. Nursing Ethics, 18(5), 662-671. Doi:10.1177/0969733011408049

Broad, J. B., Gott, M., Kim, H., Boyd, M., Chen, H., & Connolly, J. M. (2013). Where do people die? An international comparison of the percentage of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged care settings in 45 populations, using published and available statistics. International Journal of Public Health, 58(2), 257-267.

Candib, L. M. (2002). Truth telling and advanced planning at end of life: problems with autonomy in a multicultural world. Family System Health, 20, 213-228.

Casarett, D., Kutner, J. S., & Abrahm, J. (2001). Life after death: a practical approach to grief and bereavement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 134(3), 208-15.

Centers for Disease Control (2015). Leading causes of death by age group 2013. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/leading_causes_of_death_by_age_group_2013-a.pdf

Centers for Disease Control. (2016). Leading causes of death. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm 464

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Suicide rising across the US. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/

Chattopadhyay, S., & Simon, A. (2008). East meets west: Cross-cultural perspective in end-of-life decision making from Indian and German viewpoints. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 11, 165-174.

Coolen, P. R. (2012). Cultural relevance in end-of-life care. EthnoMed, University of Washington. Retrieved from https://ethnomed.org/clinical/end-of-life/cultural-relevance-in-end-of-life-care

Doka, K. (1989). Disenfranchised grief. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Dresser, N. & Wasserman, F. (2010). Saying goodbye to someone you love. New York: Demos Medical Publishing.

Ellis, J., Dowrick, C., & Lloyd-Williams, M. (2013). The long-term impact of early parental death: Lessons from a narrative study. The Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 106(2), 57-67.

Erber, J. T., & Szuchman, L. T. (2015). Great myths of aging. West Sussex, UK: Wiley & Sons.

Fox, E. (1997). Predominance of the curative model of medical care: A residual problem. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(9), 761-764. Retrieved from: http://www.fammed.washington.edu/palliativecare/requirements/FOV1-00015079/PCvCC.htm#11

Friedman, R., & James, J. W. (2008). The myth of the stages of loss, death, and grief. Skeptic Magazine, 14(2), 37-41.

Funeral Directors Association. (2017). NFDA consumer survey: Funeral planning not a priority for Americans. Retrieved from http://www.nfda.org/news/media-center/nfda-news-releases/id/2419.

Ganz, F. D. (2019). Improving Family Intensive Care Unit Experiences at the End of Life: Barriers and Facilitators. Critical Care Nurse, 39(3), 52–58.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1966). Awareness of dying. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

Green Burial Council. (2019). Green burial defined. Retrieved from https://www.greenburialcouncil.org/green_burial_defined.html

Healy, M. (2019, February 6). Steep increase in U.S. women’s OD deaths. Chicago Tribune, p. 2.

Hedegaard, H., Curtin, S., & Warner, M. (2018). Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999-2017. NCHS Data Brief, No. 330. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db330-h.pdf

Hedegaard, H., Miniño, A., & Warner, M. (2018). Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. NCHS Data Brief, No. 329. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db329-h.pdf

Herndon, E., & Joyce, L. (2004). Getting the most from language interpreters. Family Practice Management, 11, 37-40.

Heron, M. (2018). Deaths: Leading causes for 2016. National Vital Statistics, 67(6), 1-77.

Holland, J. L., Geary, N., Marchini, A., & Tross, S. (1987). An international survey of physician attitudes and practices in regard to revealing the diagnosis of cancer. Cancer Investigation, 5, 151-154.

Institute of Medicine. (2015). Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kaufert, J. M., & Putsch, R. W., (1997). Communication through interpreters in healthcare: Ethical dilemmas arising from differences in class, culture, language, and power. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 8, 71-87.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. New York: Macmillan.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1975). Death; The final stage of growth. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall. 465

Kübler-Ross, E., & Kessler, D. (2005). On grief and grieving. New York: Schribner.

Lipka, M. (2014). 5 facts about Americans’ views on life and death issues. Pew Research Institute. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/01/07/5-facts-about-americans-views-on-life-and-death-issues/

Lynn, J., & Harrold, J. (2011). Handbook for mortals (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Maciejewski, P. K., Zhang, B., Block, S. D., & Prigerson, H. G. (2007). An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(7), 716-723.

Marks, N. F., Jun, H., & Song, J. (2007). Death of parents and adult psychological and physical well-being: A prospective U. S. national study. Journal of Family Issues, 28(12), 1611-1638.

Morrison, R. S., Zayas, L. H., Mulvihill, M., Baskin, S. A., & Meier, D. E. (1998). Barriers to completion of healthcare proxy forms: A qualitative analysis of ethnic differences. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 9, 118-126.

Moss, M. S., & Moss, S. Z. (1995). Death and bereavement. In R. Blieszner and V. H. Bedford (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the family (pp.422-439). Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Narayan, C. (2016). First child dies by euthanasia in Belgium. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2016/09/17/health/belgium-minor-euthanasia/

National Cancer Institute. (2013). Grief, bereavement, and coping with loss. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/advanced-cancer/caregivers/planning/bereavement-pdq#section/_62

National Funeral Directors Association. (2019). Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.nfda.org/news/statistics.

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2019). NHPCO facts and figures: 2018 edition. Retrieved from https://39k5cm1a9u1968hg74aj3x51-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2018_NHPCO_Facts_Figures.pdf

National Institute on Health. (2007). Hospitals Embrace the Hospice Model. Retrieved from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/news/fullstory_43523.html

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2013). NHPCO’s facts and figures: Hospice care in America 2013 edition. Retrieved from http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2013_Facts_Figures.pdf

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2014). NHPCO’s facts and figures: Hospice care in America 2014 edition. Retrieved from http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2014_Facts_Figures.pdf

Newson, R. S., Boelen, P. A., Hek, K., Hofman, A., & Tiemeier, H. (2011). The prevalence and characteristics of complicated grief in older adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 132(1-2), 231-238.

Office of the Inspector General. (2018). Vulnerabilities in the Medicare Hospice Program Affect Quality Care and Program Integrity: An OIG Portfolio. U.S. Department of Health and Human Service. Retrieved from https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-16-00570.pdf

Oregon Public Health Division. (2016). Oregon Death with Dignity Act: 2015 data summary. Retrieved from https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year18.pdf

Parkes, C. M., & Prigerson, H. G. (2010). Bereavement: Studies of grief in adult life. New York: Routledge.

Pattison, E. M. (1977). The experience of dying. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall.

Pew Research Center. (2013). Views on end-of-life medical treatment. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/2013/11/21/views-on-end-of-life-medical-treatments/

ProCon.org. (2019). State-by-state guide to physician-assisted suicide. Retrieved from http://euthanasia.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=000132 466

Redfoot, D., Feinberg, L., & Houser, A. (2013). The aging of the baby boom and the growing care gap: A look at future declines in the availability of family caregivers. AARP. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/ltc/2013/baby-boom-and-the-growing-care-gap-insight-AARP-ppi-ltc.pdf

Schechter, H. (2009). The whole death catalog. New York: Ballantine Books.

Searight, H. R., & Gafford, J. (2005a). Cultural diversity at end of life: Issues and guidelines for family physicians. American Family Physician, 71(3), 515-522.

Searight, H. R., & Gafford, J. (2005b). “It’s like playing with your destiny”: Bosnian immigrants’ views of advance directives and end-of-life decision-making. Journal or Immigrant Health, 7(3), 195-203.

Shannon, J. B. (2006). Death and dying sourcebook. Detroit, MI: Omnigraphics.

Stanford School of Medicine. (2019). Where do Americans die? Retrieved https://palliative.stanford.edu/home-hospice-home-care-of-the-dying-patient/where-do-americans-die/

Stroebe, M. S., & Schut, H. (2001). Meaning making in the duel process model of coping with bereavement. In R. A. Neimeyer (Ed.), Meaning, reconstruction and the experience of loss (pp. 55-73). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Stroebe, M. S., Schut, H., & Stroebe, W. (2005). Attachment in coping with bereavement: A theoretical integration. Review of General Psychology, 9, 48-66.

Sweeting, H., & Gilhooly, M. (1997). Dementia and the phenomenon of social death. Sociology of Health and Illness, 19, 93–117.

Taylor, S. E., Kemeny, M. E., Reed, G. M., Bower, J. E., & Gruenewald, T. L. (2000). Psychological resources, positive illusions, and health. American Psychologist, 55(1), 99-109.

Telford, K., Kralik, D., & Koch, T. (2006). Acceptance and Denial: Implications for People Adapting to chronic illness: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 55, 457-464.

Uniform Law Commissioners. (1980). Defining death: medical, legal and ethical issues in the definition of death. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1981159–166.166

Weir, K. (2019). Worrying trends in U.S. suicide rates. Monitor on Psychology, 50(3), 24-26.

Weitz, R. (2007). The sociology of health, illness, and health care: A critical approach (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

Worden, J. W. (2002). Children and grief: When a parent dies. London: Guilford Press.

Worden, J. W. (2008). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner (4th ed.). New York: Springer Publishing company.

World Health Organization. (2018). Top 10 causes of death. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/causes_death/top_10/en/

Youdin, R. (2016). Psychology of aging 101. New York: Springer Publishing Company.